|

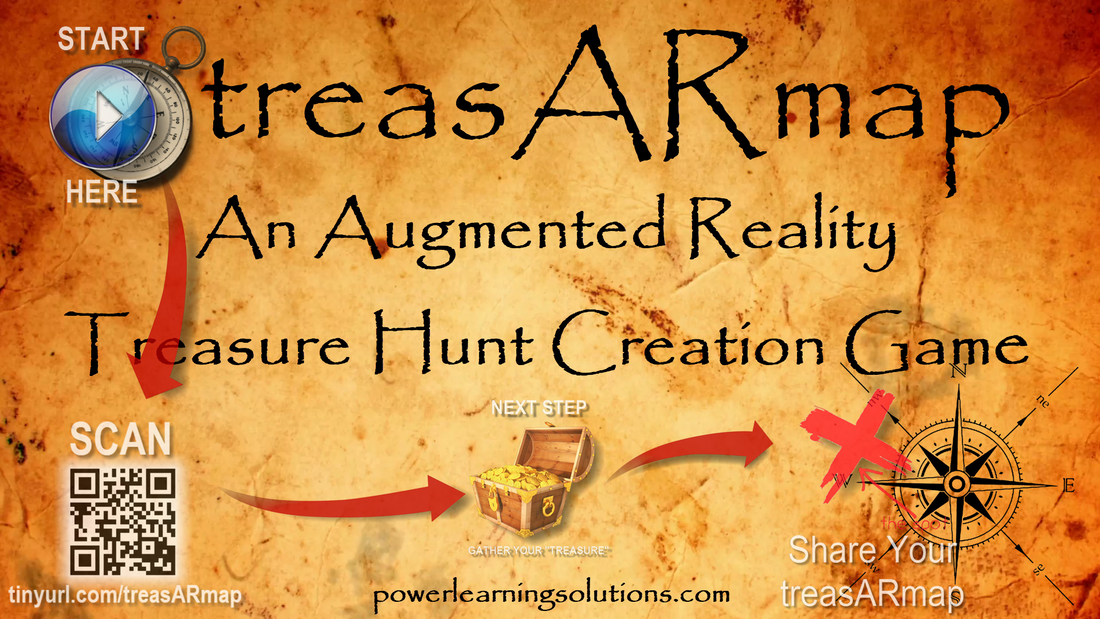

I've been playing around a bit with using HP Reveal Studio (formerly Aurasma Studio) to created Augmented Reality resources, such as interactive game boards and conference posters. For Mobile Summit 2018 and the 17th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning (mLearn 2018), I developed a workshop on how to use HP Reveal Studio to create an AR treasARmap. That's a magic treasure map that appears blank for my students, until they scan it using the HP Reveal (formerly Aurasma) app using their mobile devices. What they see when they scan the blank map is something like the image below, where the pieces of the map slowly reveal themselves.

The QR code and URL on the image above will take you to the companion resources that I created for the workshops. But, since I've had a lot of requests for this, I've put together this blog post to bring everything together into one spot, and show how I created the AR treasARmap.

About treasARmap

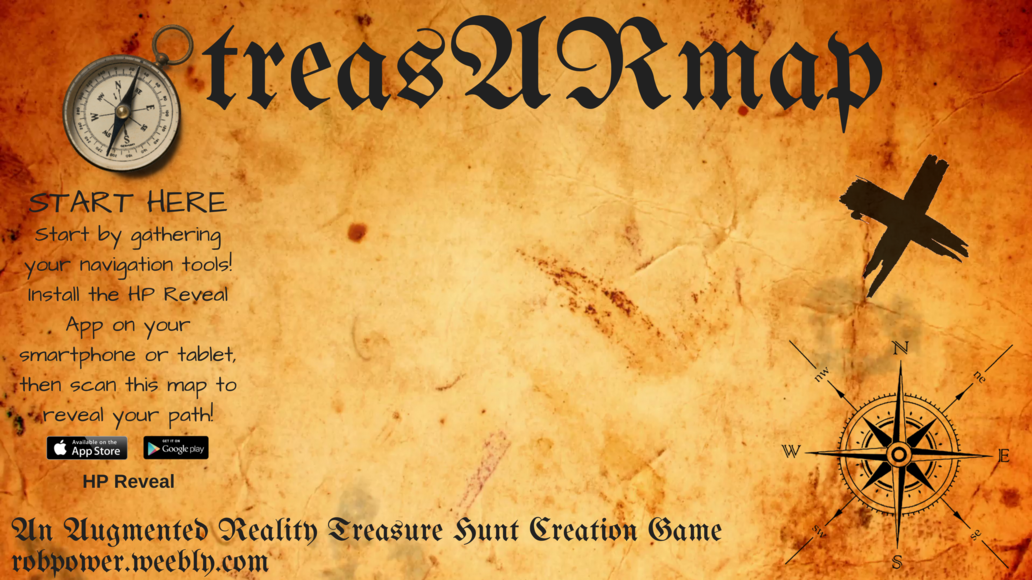

The treasARmap map was created using the Canva free online poster and infographic creation suite. It was then "augmented" using a free HP Reveal Studio account. This is what the final product looks like:

Accessing the Hidden Treasure Map

To access this augmented reality "treasARmap," install the HP Reveal (formerly Aurasma) AR app on your mobile device. Launch the app, point your device at the image below, and click on the AR objects to follow a team's path to the finish line!

Get the App

Follow Rob Power, EdD on HP Reveal

Step 1: Making a treasARmap Poster

Do It Yourself

Additional Useful Tutorials

Step 2: Augmenting Your treasARmap

Do It Yourself

Additional Useful Tutorials

Share Your treasARmap

I'd love to see what you come up with playing around with the concept of creating AR treasARmaps, or other AR resources for your teaching and learning! I've set up the following Padlet wall as a spot where participants in the treasARhunt workshops can share their completed projects... but feel free to post yours, as well. (Just be sure to include a note as to "who" we need to follow using the HP Reveal app to bring your treasARmap to life!)

1 Comment

I seem to have occasion to repost my most viewed blog post to date once every few months, as the discussions around blanket bans on mobile devices in schools rear their ugly heads once again. This time, it's talk from the newly elected Progressive Conservative government in Ontario, Canada, who are placing a blanket ban on mobiles on the table as part of their incoming platform (Flanagan, 2018). (A few months back, it was the blanket ban on cell phones in schools in France (Willsher, 2017).) So... here it is again... reposted here so that this March 2016 post from my old blog site, the xPat_Letters Blog, has a new home (and new context) here on the brand new Power Learning Blog. Ban First, Ask Questions Later... The Problem with Calls to Ban Mobile Devices (updated) (originally posted March 2, 2016) I read the article Schools that Ban Mobile Devices See Better Results on the bus this morning. It is from May 2015, but someone had reposted the @guardian piece to my @Twitter feed. From my perspective as a mobile learning researcher, it presented troubling research findings: "Effect of ban on phones adds up to equivalent of extra week of classes over a pupil’s school year" (Doward, 2015) But, they’re not troubling for the obvious reason presented in the story. The premise of the story (and the research on which it was based) was that mobile devices are distracting students to the level of significant lost instructional time. And if schools want to see better test scores, then they had better start banning mobile devices. No. This is not the problem. A blanket ban on mobile devices because they distract learners is just the latest in a centuries-old trend of resisting technological change out of fear of the unknown. Steve Howard (2012, July 14) pointed out that as far back as 1815 a school principal fought against the introduction of paper and ink, and lamented that: Students today depend on paper too much. They don’t know how to write on a slate without getting chalk dust all over themselves. They can’t clean a slate properly. What will they do when they run out of paper? If we want to leverage new technologies to enhance learning experiences and bridge current inequities in the classroom, then we cannot succumb to knee-jerk reactions to alarmist statistics. As Homer Simpson once said: What IS troubling with this story (and research) are the questions that were NOT asked. The research shows an increase in achievement across ALL schools that have banned mobile devices versus ALL schools that allow them. BUT, no attempt is made to look at schools that actually plan for mobile technology integration. It could be that the majority of the schools polled have no such plans, in which case the argument that mobile devices only serve to distract students is likely true. But what of schools that have coordinated their technological infrastructure and pedagogical strategies to leverage mobile devices within the curriculum? I have predicated my mobile learning research to date on the problem that teachers and schools are the barriers to effective integration of mobile technologies because they lack confidence in the technology. The problem is NOT that mobile devices are allowed into schools. The problem is that we are not preparing teachers and schools for an environment of ubiquitous access to technology. From my dissertation (Power, 2015, p. 11): Ally (2014) noted that teacher training continues to be based on an outdated education system model that does not adequately prepare teachers to integrate mobile technologies into teaching practice. Lack of training in the pedagogical considerations for the integration of a specific type of technology can have a negative impact upon teachers’ perceptions of self-efficacy (Kenny et al, 2010). Technology will never replace good teachers. But technology can make good teachers better. Better teacher (and school) preparation will enable educators to make instructional design decisions that incorporate technology, and increase student engagement and access to learning opportunities and resources. My research has shown that professional development focused on scaffolding technology integration in the context of desired learning outcomes and appropriate pedagogical decisions does increase teachers’ interest and confidence in using educational technology. If teachers are interested, and plan how they will leverage technology in the classroom, then distraction will decrease and learning will improve. However, preparing teachers to leverage educational technology is not enough. We must also prepare students. Yes, if you let students who have had no guidance access mobile devices, then there is huge potential for them to be distracted. But, if you teach them digital citizenship and responsible use, there is less likelihood of distraction. And they will be better prepared for a world with near universal technology permeation. You cannot teach digital citizenship or responsible technology use with black and white policies of either banning all devices, or letting them all in. Unfortunately, the information technology support departments (and bureaucracies) of too many school systems (and higher education institutions) still operate with Acceptable Use Policies, which explicitly detail what is permissible and what is not. In contrast, Responsible Use Policies focus on making appropriate decisions about when and how to use technology. (Joe Countryman, Mary-Ann Vardakas & Melissa Taffe did a presentation on this, and prepared a wikipage about it for a Problem-Based Learning activity in the Digital Tools for Knowledge Construction course I teach at University of Ontario Institute of Technology.) Before policy makers, or the public at large, jump to the conclusion that the statistics presented in the Guardian (and also on CNN) point to the need for an outright ban on mobile devices in education, a number of questions should be considered:

References

Ally, M. & Prieto-Blázquez, J. (2014). What is the future of mobile learning in education? Mobile Learning Applications in Higher Education [Special Section]. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento (RUSC), 11(1), 142-151. doi http://doi.dx.org/10.7238/rusc.v11i1.2033 Countryman, J., Vardakas, M., & Taffe, M. (2016). Acceptable use policies. Retrieved from http://educ5101jmm.pbworks.com/w/page/104432989/PBL%201%20-%20Group%204%20-%20Acceptable%20Use%20Policies Doward, J. (2015, May 16). Schools that ban mobile phones see better academic results. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/may/16/schools-mobile-phones-academic-results Flanagan, R. (2018, May 30). PC platform includes ban on cellphones in schools. CTV News Kitchener. Retrieved from kitchener.ctvnews.ca/pc-platform-includes-ban-on-cellphones-in-classrooms-1.3952316#_gus&_gucid=&_gup=twitter&_gsc=Qi5DSUU Howard, S. (2012, July 14). The ruin of education in our country – A positive thing [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://stevehoward999.wordpress.com/2012/07/14/the-ruin-of-education-in-our-country-a-positive-thing/ Kenny, R.F., Park, C.L., Van Neste-Kenny, J.M.C., & Burton, P.A. (2010). Mobile self-efficacy in Canadian nursing education programs. In M. Montebello, V. Camilleri and A. Dingli (Eds.), Proceedings of mLearn 2010, the 9th World Conference on Mobile Learning, Valletta, Malta. METTL (2015). The Homer Simpson guide to online assessments [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://mettl.com/blog/2015/08/the-homer-simpson-guide-to-psychometric-assessments/ Power, R. (2015). A framework for promoting teacher self-efficacy with mobile reusable learning objects (Doctoral dissertation, Athabasca University). Available from http://hdl.handle.net/10791/63 Power, R. (2016, March 2). Ban First, Ask Questions Later... The Problem with Calls to Ban Mobile Devices. [Web log post]. The xPat_Letters Blog. Available from http://robpower74.blogspot.com/2016/03/ban-first-ask-questions-later-problem.html Willsher, K. (2017, December 11). France to ban mobile phones in schools from September. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/11/france-to-ban-mobile-phones-in-schools-from-september |

AuthorRob Power, EdD, is an Assistant Professor of Education, an instructional developer, and educational technology, mLearning, and open, blended, and distributed learning specialist. Recent PostsCategories

All

Archives

June 2024

Older Posts from the xPat_Letters Blog

|

||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed