Why do some superstitions and myths linger? Is it because they have some kernel of truth that will help guide us through an uncertain and increasingly complex world? Or is it because they sound like an easy-to-understand truth, that explains life's complexities in a way that makes it easy for us to justify otherwise irrational actions? Always influencing our decisions, yet threatening to undermine our intentions because of their inherent lack of scientific merit? In the case of the concept of Learning Styles, I fear it is the latter option. The spectre of "learning styles," and its proclaimed "importance" as a consideration in instructional design, continues to loom over education systems -- despite well-informed entreaties to abandon the myth in favor of evidence-informed decision-making. I recently asked a group of graduate-level education students to draft position papers on their personal teaching philosophies with respect to the integration of educational technology. We had spent the first few weeks of the course discussing the core competencies of Instructional Designers, and exploring a range of key learning theories. Not once in the course readings were Learning Styles included as a fundamental concept. Yet... the concept has popped up in Tweets using the course hashtag, and in a number of students' teaching philosophy statements. I don't normally discuss Learning Styles in my courses, because they are not only unproven -- they are disproven. Corporal punishment was once also considered acceptable in schools. But -- unlike corporal punishment -- the myth of Learning Styles remains so pervasive in schools, colleges, and universities, that I feel I would be remiss if I didn't address it in some way. If the brilliant and creative educators whom I have the privilege of collaborating with every day are being affected by this insidious myth, then I feel I should at least give them some "food for thought" -- some fuel for a healthy debate, rather than letting blind acceptance of something that has been "debunked" continue unchecked. I am not a neuroscientist, and there are plenty of reputable authors who have commented on this topic more eloquently than I could... so I will not pontificate. I will summarize a few key points, and point to some of these excellent resources that every instructional designer, practicing educator, and education student should take the time to read. What is the Learning Styles Myth?As Donald Clark (2016) noted, Learning Styles are distillations of myriad learning theories into "simple models... which are simplistic, easy to learn, easy to put on a training Powerpoint slide, and easy to explain." They distill complex learning theories into simple categories of how students "learn best," focusing on their preferred modes of receiving and interacting with learning content. Learning-styles-online.com (n.d.) list the following seven categories, with which I'm certain most educators are familiar: What's Wrong with These Learning Styles?As Clark (2016) laments, "they are represented as researched, evidenced and science, when they are not." Clark has published a number of blog posts discussing the lack of science behind the Learning Styles myth and the reasons why it is still so (alarmingly) pervasive, which are well-worth reading:

Likewise, Steven Wheeler (2011) posted an excellent summary of what he called A Convenient Untruth. Some Key Points from Clark, Wheeler, and the many academic sources they cite (which include both neuroscientists and educational researchers):

The gist of a recent Tweet by one of my graduate education students (while sharing a link to an article from Forbes (McCue, 2019) espousing the importance of Learning Styles) was that incorporating them into instructional decision-making helps more students to achieve learning goals, because we'll hit more of their preferred "styles." Without getting into too much science -- targeting Learning Styles preferences should not be the focus. But, there is evidence-based merit to incorporate a variety of teaching and learning approaches. Such variety increases engagement, because it reduces the "normalization" of instructional presentation. In other words, it prevents desensitization to the presentation format. It also peaks learners' interest -- ALL learners, not just those who prefer one "style" over another. Boredom can take students out of the engagement zone talked about in Flow theory (Learning-theories.com, n.d.)! Then, there's also the benefit of multi-modal, or multi-channel reception of content (Mareno & Mayer, 2000; Quinette, et al., 2003; Zheng, 2009) . Evidence has shown that information presented through multiple modes -- targeting multiple senses -- is better understood, and better encoded into long-term memory. Long story short -- there are plenty of valid, rigorously tested learning theories and models that we should be considering when making instructional design decisions. There are plenty of reasons to incorporate variety in how we present material, and expect our students to interact with it. There is not only NO need to rely upon over-simplified models that sound good (but lack evidence) -- reliance on such models leads us astray from informed decision-making (and potentially risks us making harmful instructional decisions). ReferencesClark, D. (2010, February 15). Learning Styles - final nail in coffin? [Web log post]. Donald Clark: Plan B. Available from http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.com/2010/02/learning-styles-final-nail-in-coffin.html

Clark, D. (2016, October 8). 7 reasons why teachers believe, wrongly, in ‘Learning Styles.' [Web log post]. Donald Clark: Plan B. Available from http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.com/2016/10/7-reasons-why-teachers-believe-wrongly.html Clark, D. (2018, June 16). University faculty believe in Learning Styles and promote it to students while their Teacher Training departments say it's a myth. [Web log post]. Donald Clark: Plan B. Available from http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.com/2018/06/university-faculty-believe-in-learning.html ClipartXtras (n.d.). Chalkboard. [Image file]. Available from https://clipartxtras.com/categories/view/de245518959d7fb4318c464ae3016506010232ea/chalkboard-clipart-transparent.html Kisspng (2019). Chalkboard eraser. [Image file]. Available from https://www.kisspng.com/png-chalkboard-eraser-blackboard-sidewalk-chalk-2228618/download-png.html Learning Styles Online (n.d.) Overview of Learning Styles. [Web page]. Available from https://www.learning-styles-online.com/overview/ Learning-theories.com (n.d.) Flow (Csíkszentmihályi). [Web page]. Available from https://www.learning-theories.com/flow-csikszentmihalyi.html Mareno, R. & Mayer, R. E. (2000). A learner-centered approach to multimedia explanations: Deriving Instructional Design principles from Cognitive Theory. Interactive Multimedia Electronic Journal of Computer-Enhanced Learning, 2(2). http://imej.wfu.edu/articles/2000/2/05/index.asp McCue, T.J. (2019, January 30). How Combined Learning Style Not Just Visual Or Kinesthetic Can Help You Succeed. [Web log post]. Forbes. Available from https://www.forbes.com/sites/tjmccue/2019/01/30/how-combined-learning-style-not-just-visual-or-kinesthetic-can-help-you-succeed/#5f329857d9cc PlusPNG (2019). Regular Zombie. [image file]. Available from http://pluspng.com/png-7866.html Quinette, P., Guillery, B., Desgranges, B., de la Sayette, V., Viader, F., & Eustache, F. (2003). Working memory and executive functions in transient global amnesia. Brain 126(9), 1917-1934. Available from https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg201 Wheeler, S. (2011, November 24). A convenient untruth. [Web log post]. Learning with 'e's. Available from http://www.steve-wheeler.co.uk/2011/11/convenient-untruth.html Zheng, R. Z. (2009). Cognitive effects of multimedia learning. [PDF file]. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. http://www.sci.sdsu.edu/CRMSE/personal_pages/sreed/Manipulating_Materials.pdf

1 Comment

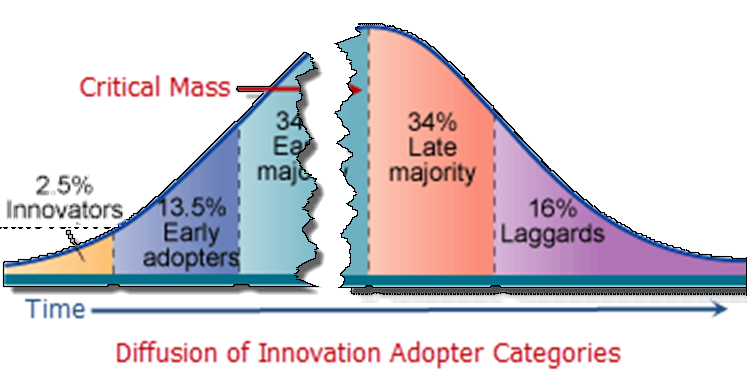

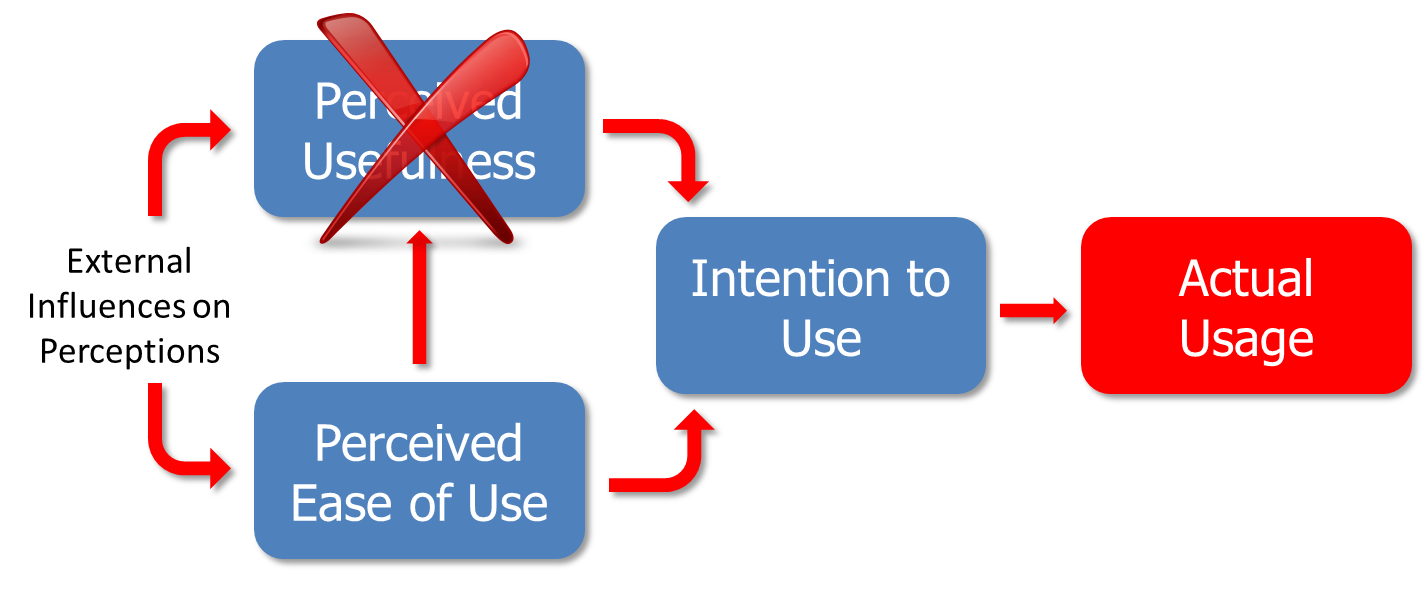

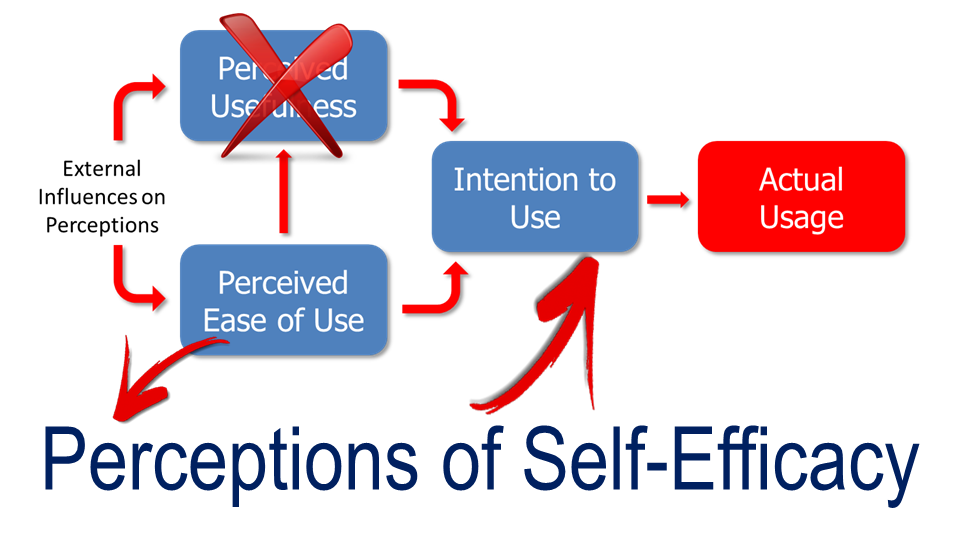

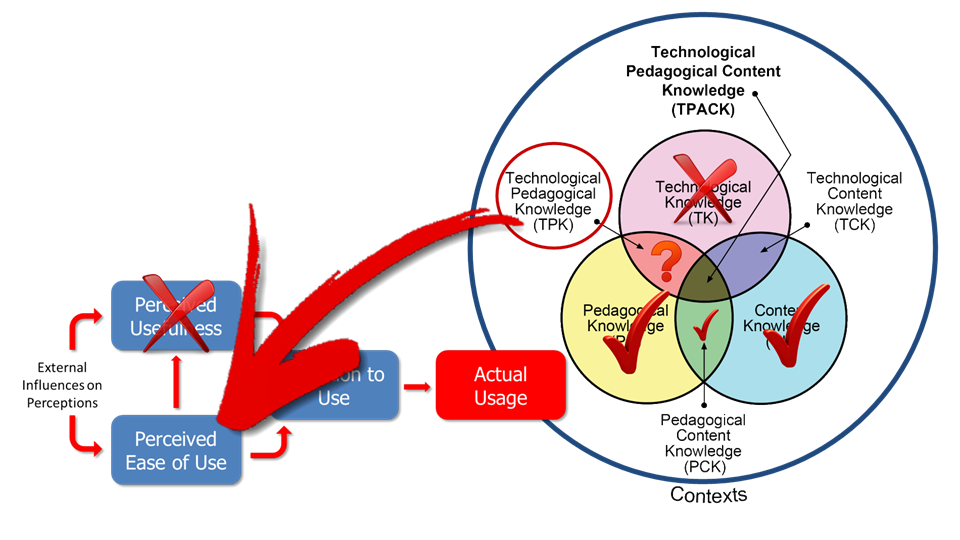

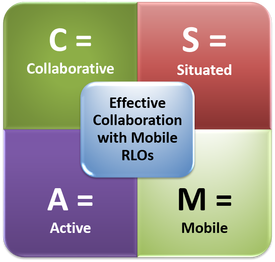

What are the challenges that we face as technology integration specialists in our teaching and learning contexts? And, what tips or advice do you have for overcoming some of those hurdles? Those are questions that I just posed to graduate education students participating in my Spring/Summer 2018 section of EDUC5303G: Technology and the Curriculum. From my experience (and from my chapter in Yu, Ally and Tsanikos (2018) and my keynote presentation at Mobile Summit 2018)... One of the biggest hurdles that we seem to face is getting past shifting into the "Early Adopters" or very early "Early Majority" phases of the Diffusion of Innovation model (Rogers, 1974): If we look at the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989), I don't think that the problem with intention (and action) to integrate technology lies with "Perceptions of Usefulness." We see examples every day of how useful different technologies can be. Digital technologies can do just about anything that we can dream up for them to do... and examples of innovative EdTech use abound. It's easy to find them, and it's easy to share them. (That doesn't mean we should slack off on our efforts in this area... ideas and inspiration are still of vital importance.) So... if the problem is not with "Perceptions of Usefulness" in TAM, it must be with "Perceived Ease of Use." It's pretty reasonable to understand the causes of this problem. Ally and Tsinakos (2014) lament that our teacher preparation programs are largely still preparing teachers to function in a system that hasn't really existed since the 1980s. Finger, Jamieson-Proctor and Albion have similarly lamented that changes in digital technologies that could benefit the curriculum: "have not always translated into practice which has resulted in a focus on the need for improvements in pre-service teacher education programs and professional development of practising teachers” (2010, p. 114) The Self-Confidence ProblemThe biggest problem we face in getting teachers to integrate technology into their practice isn't that they don't see it as useful... it's that they don't feel comfortable using it. They lack a strong perception of self-efficacy. As Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) note: Perceptions of self-efficacy can influence a teacher’s “levels of planning and organization” and “willingness to experiment with new methods to meet the needs… of students” (p. 783). If we can help teachers to feel more comfortable with using technology, and they already see that technology as being potentially useful, they'll be more likely to experiment with it in their teaching and learning practice. So... how do we get there? Filling the Gaps in TPACKIn my Handbook chapter, and Mobile Summit 2018 Keynote, I focused in on how widespread TPACK (Koehler & Mishra, 2006, 2008; TPACK.org, 2012) has become in guiding teacher professional development when it comes to technology integration. As teachers, we already have strengths in the areas of Content Knowledge and Pedagogical Knowledge. It's easy for us to demonstrate the usefulness of different technologies, and to find training or resources on the technical how-to of technologies that we do choose to integrate (assuming that we can find the time to pursue them!). So we've got those aspects of TPACK covered off pretty well. And, if we're using TPACK to help shape professional development based on our needs as teachers, then we don't need to focus so much on addressing those areas. But, what TPACK shows us we're still missing, and fails in-and-of-itself to deliver, is the actual Technical-Pedagogical Knowledge area. Without this understanding of pedagogical decision-making for the use of technology, how are teachers going to increase their confidence in their ability to use technology effectively? Focusing on Good PedagogyAs I've already noted, teachers are pedagogical professionals. If we want to increase their self-efficacy when it comes to meaningfully and effectively integrating technology into their practice, we don't need to focus on either the usefulness of the technology, or how to use specific tech tools or "apps du-jour." What we need to focus on is how to make pedagogical decisions first, decide when tools are needed, and then find appropriate tools to "get the job done." In my research, I've demonstrated exactly what Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) were talking about. When provided with tools to support pedagogical decisions around the use of technology, teachers became both more interested in, and more willing to experiment with technologies they hadn't used before. In my research, I focused on the use of mobile learning strategies, and I provided teachers with professional development that focused on making instructional design decisions using an evidence-driven framework. They did get to the "fun" bit of playing with the tech itself (I mean, how boring would PD be if we never got a chance to play with the toys!) -- but I carefully minimized the cognitive load of learning new technologies, so that the teachers could focus on the technology integration decisions that they were making. The Key Takeaway: Purpose and PedagogyWhat's the point of my rant in this blog post? While we should keep up with experimenting with innovative technology use in education, our main concern should not be with either what the technology can possibly do, or how to use that technology. The focus should be on how to use the technology meaningfully. To get there, we need to place sufficient focus in teacher preparation programs and professional development efforts on how to make decisions about when it's appropriate to use technology tools, and how to frame our instructional design decisions. If teachers feel confident as to why they are using tools, and in the fact that it's not so important that they be experts with all of the tools themselves (after all -- our students can oftentimes provide us with on-the-spot tech support!), then their self-efficacy will go up. That will get more teachers to the "Intention to Use" stage in TAM, which will bring us closer to the Late Majority stage in the Diffusiion of Innovation model. You can find my full slidedeck from my Mobile Summit 2018 keynote presentation HERE. You can learn more about my research into the CSAM framework HERE, and the mTSES tool that I used to measure changes in teachers' perceptions of self-efficacy with mobile learning HERE. ReferencesAlly, M., & Tsinakos, A. (2014). Increasing access through mobile learning. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Athabasca University Press and the Commonwealth of Learning. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=466

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. doi:10.2307/249008 Finger, G., Jamieson-Proctor, R., Albion, P. (2010). Beyond pedagogical content knowledge: The importance of TPACK for informing preservice teacher education in Australia. In M. Turcanyis-Szabo & N. Reynolds (Eds.), Key competencies in the knowledge society (pp. 114-125). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 109(6), 1017-1054. Retrieved from http://punya.educ.msu.edu/publications/journal_articles/mishra-koehler-tcr2006.pdf Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. In AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.), The handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators (pp. 3-29). American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education and Routledge, NY, New York. Power, R. (2018). The CSAM framework. [Web page]. Power Learning Solutions. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/csam.html Power, R. (2018, May 16). Making mobile learning work for educators and students. Opening keynote address at Mobile Summit 2018, 16-17 May 2018, Scarborough, ON, Canada. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/making-mobile-learning-work.html Power, R. (2018). The Mobile Teacher's Sense of Efficacy Scale (mTSES). [Web page]. Power Learning Solutions. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/mtses.html Power, R. (2018). Supporting mobile instructional design with CSAM. In S. Yu, M. Ally, & A. Tsanikos (Eds.), Mobile and ubiquitous learning: An international handbook, pp. 193-209. Singapore: Springer Nature. DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-6144-8_12. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6144-8_12 Rogers, E. (1974). New product adoption and diffusion. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(4), 290–301. tpack.org (2012). The TPACK image. Retrieved from http://www.tpck.org/ Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing and elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783-805. |

AuthorRob Power, EdD, is an Assistant Professor of Education, an instructional developer, and educational technology, mLearning, and open, blended, and distributed learning specialist. Recent PostsCategories

All

Archives

June 2024

Older Posts from the xPat_Letters Blog

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed