|

It's more of an "i before e" than a "never do this" rule...  One of my instructional design students recently raised a good question about the use of color to emphasize text in digital documents (one that warrants a bit of a "mea culpa" on my part!). In the first weeks of the term, I advised students to avoid highlighting text or using colored fonts for emphasis. Then, in a recent response to another student's discussion forum questions, I highlighted her questions to set them apart from my responses. The recent question was along the lines of "you told us never to highlight text because it is a digital accessibility violation, but you just highlighted text in your post... can you clarify?" Is it Ever Okay to Use Color for Emphasis?So... my "mea culpa." My initial advice came across as a "hard and fast" rule -- NEVER use color for emphasis. The truth is, it is a bit more like the "i before e" rule of English spelling than an absolute. There are plenty of exceptions to the "i before e" rule in the English language. And, there are plenty of nuances to the "rules" around using color for emphasis of text in instructional design. In my early course advice, I didn't get into these nuances because we'll be exploring digital accessibility basics for instructional design in more detail later in the course (as students are building ID pilot projects). The original student had highlighted some key points in a discussion post for emphasis, and another student had configured all of their discussion posts to use a purple font. So, I brought up the topic of the use of color for emphasis a bit early, to get my students thinking about how to avoid creating unnecessary barriers for their reading audiences (kind of like how primary school teachers emphasize the "i before e" rule in the early grades, and let students learn the exceptions and nuances of English spelling later on). The truth is, you CAN use colored text or highlighted text for emphasis. BUT, it ONLY works for "sight" readers who have no visual acuity issues. Such techniques will cause issues if:

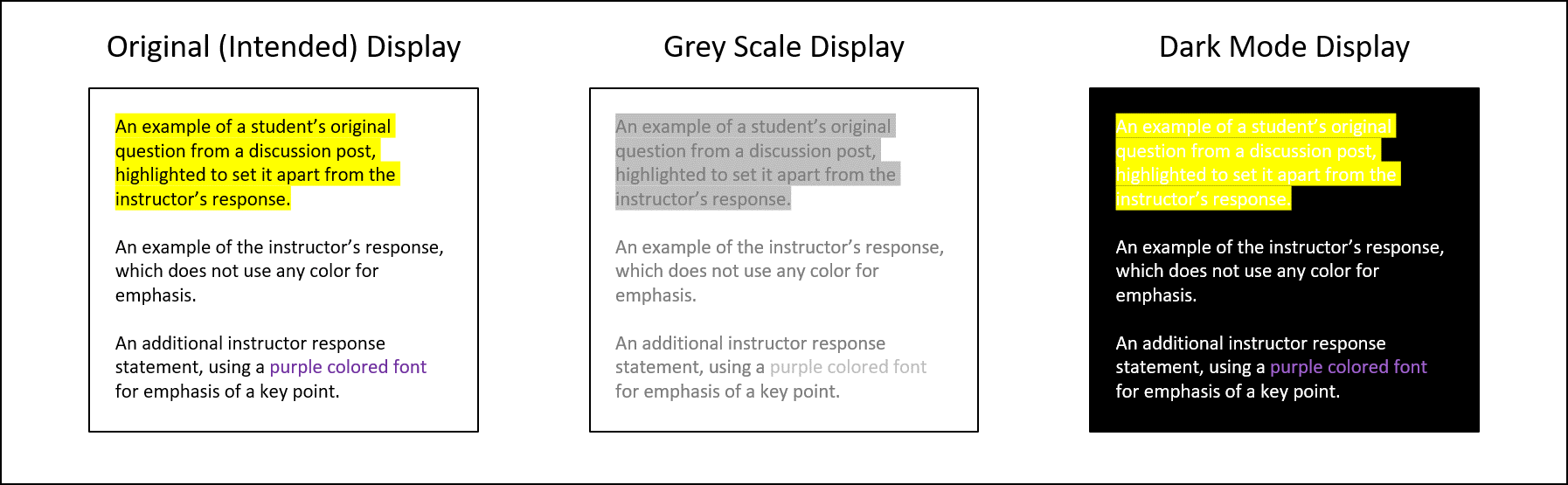

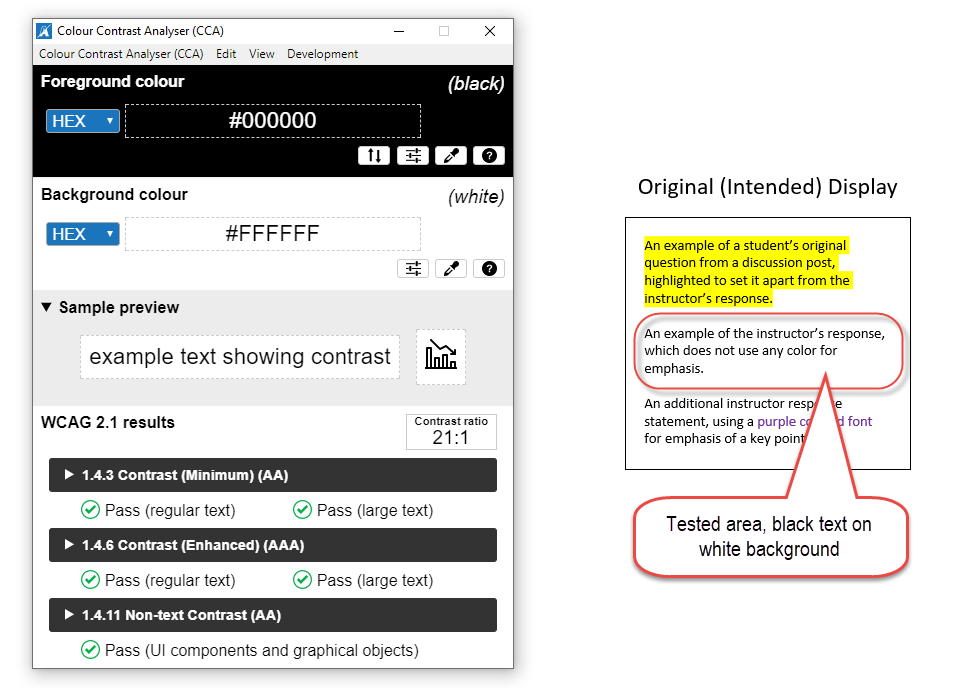

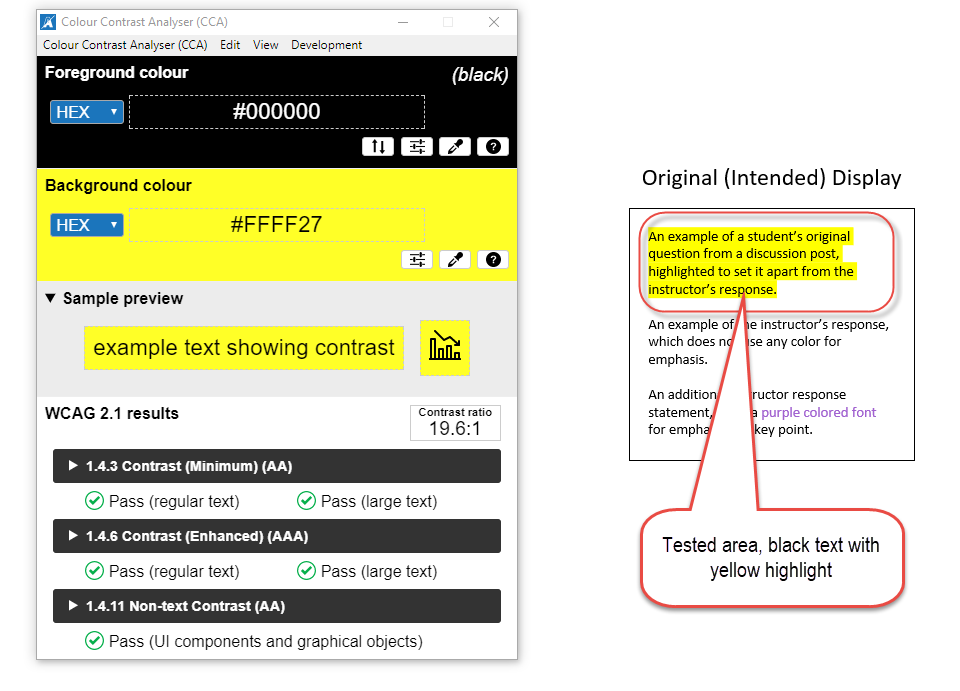

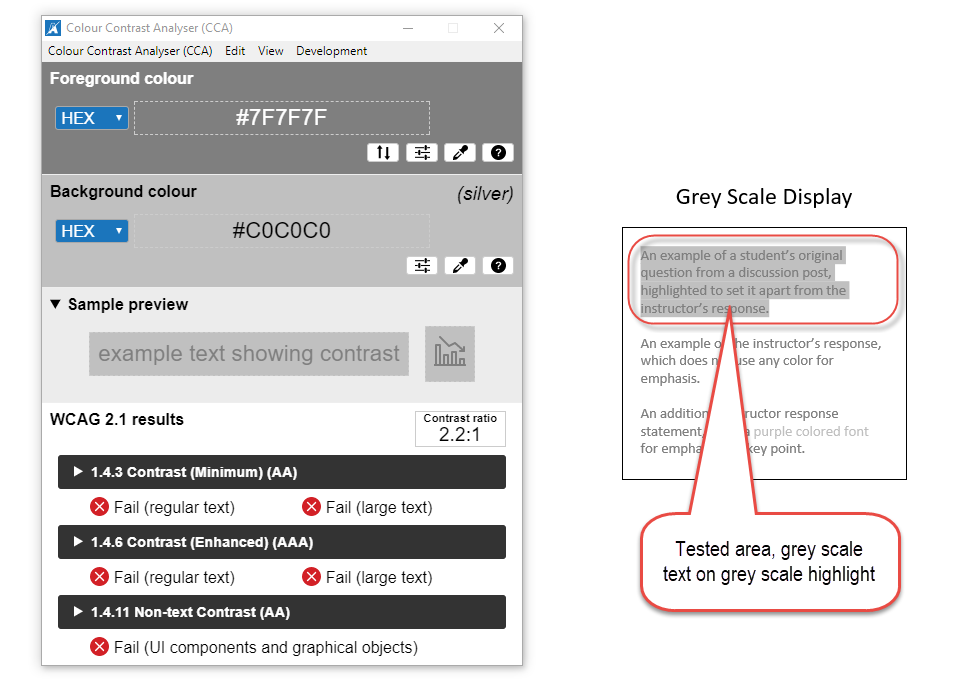

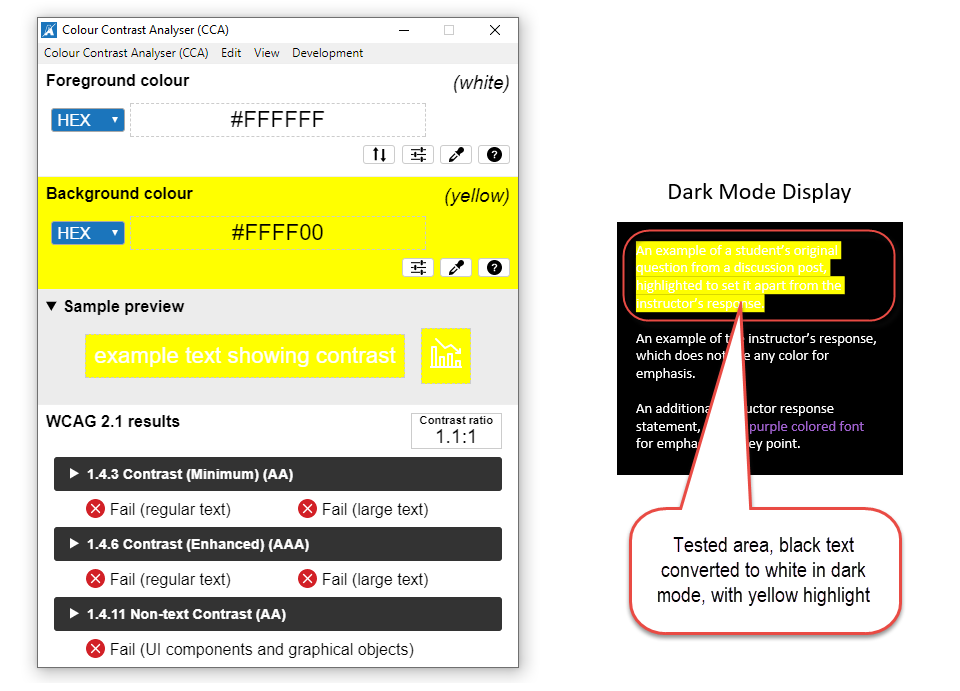

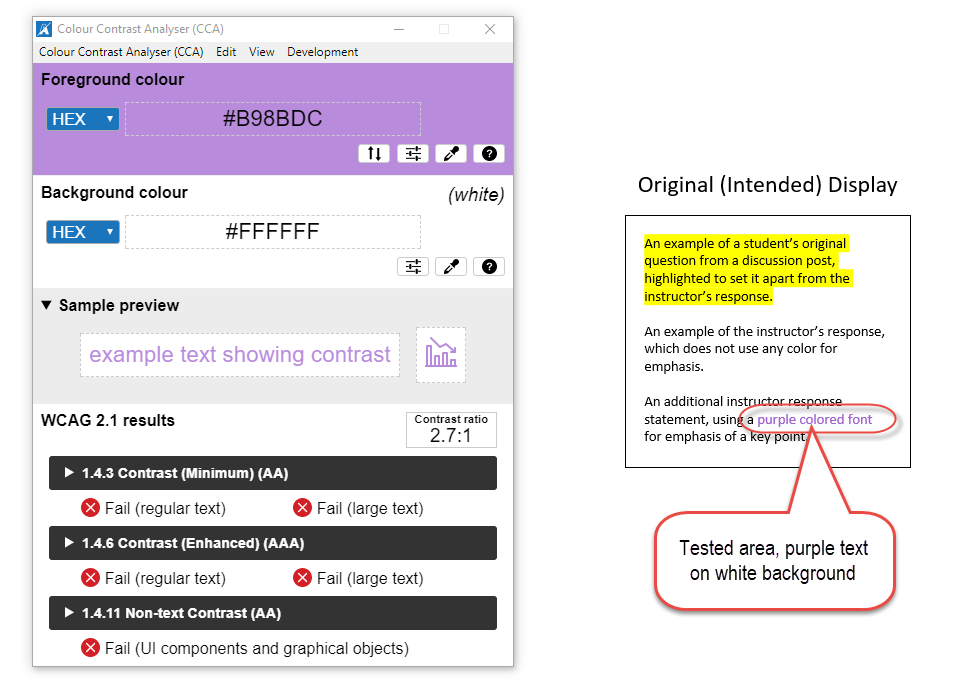

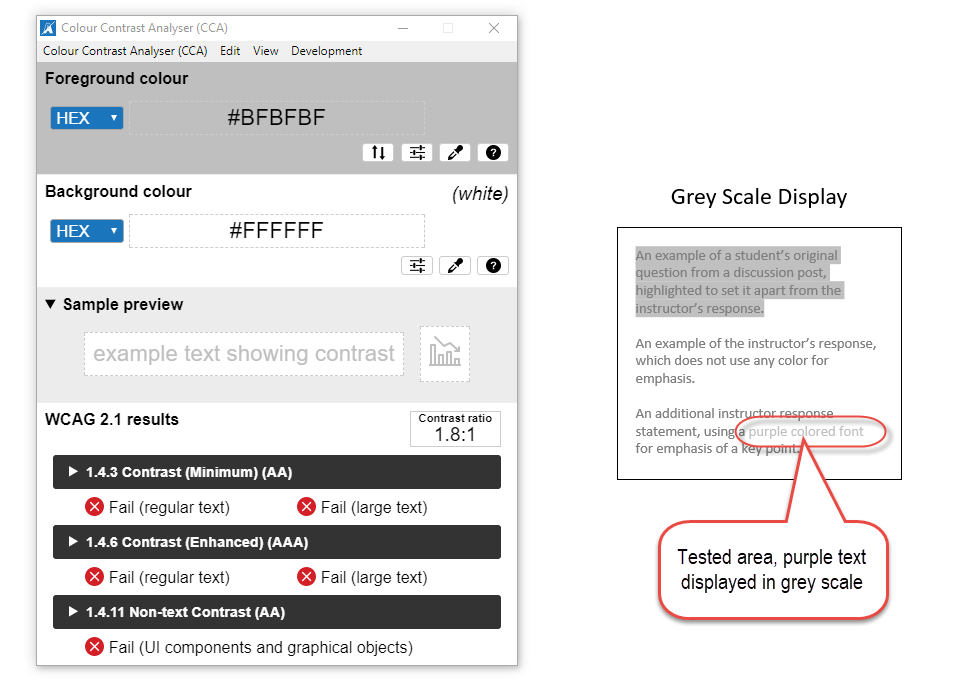

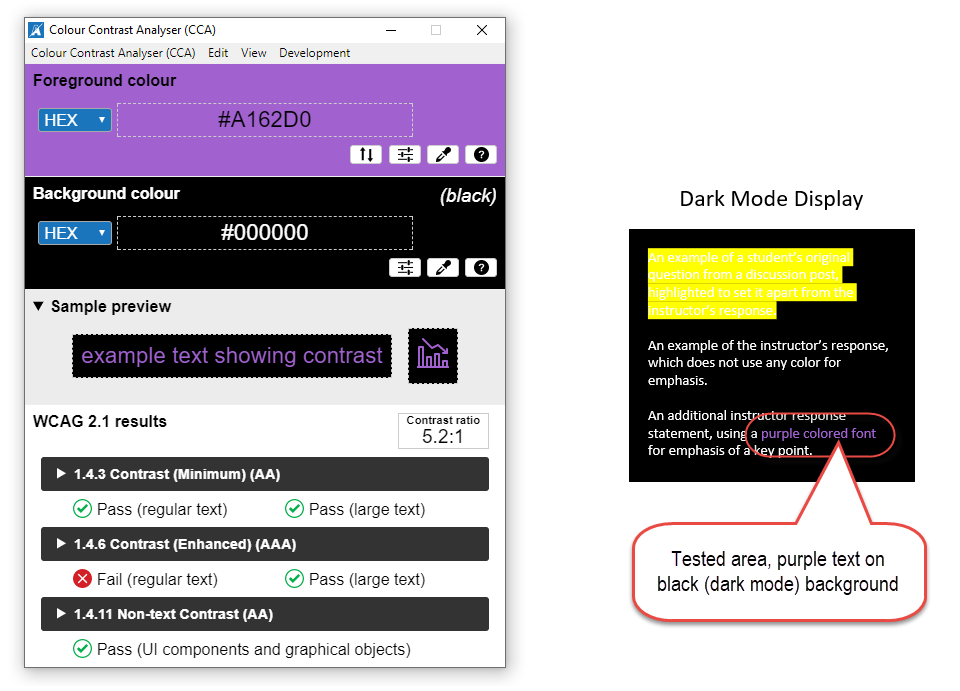

So... you CAN use color for emphasis. BUT, you must carefully consider the potential unintended consequences for your audience! The best strategy is to avoid using colored text or highlighted text unless absolutely necessary. That will avoid all of the issues noted above. Another strategy is to include some additional form of emphasis to grab the attention of "audio" readers, such as adding a graphical icon with appropriate ALT text like the following: It is important to use strategies that will indicate emphasis for anyone using a screen reader application. In the example above, the "alert" icon creates additional emphasis for "sighted" readers. It also contains the ALT text "This is an important point!," which will be read aloud to "audio" readers who are using screen reader applications. Finally, you should always "test" your product before sharing it. You can use a color contrast analyzer tool like the free Colour Contrast Analyzer available from TPGI (2024). When testing color contrast ratios (the perceptive differences between the foreground (text) and background (page or screen) colors), be sure to also test the ratios when displaying the content in grey scale, and when displaying the content on a dark mode screen. Here's how that would look using a sample of the text like what I shared (using yellow highlighted text, and some text with a purple font) via our course discussion forum: Testing Color ContrastLet's take a look at the results of color contrast tests on each text display version to see where we run into potential accessibility issues. Default (Black on White) Text: Testing the Highlighted Text: As you can see, the yellow highlighted text that I used in my discussion forum post is still readable, and passes all levels of WCAG standards for digital accessibility (World Wide Web Consortium, 2023). But, how about when that text is viewed in grey scale or on a "dark mode" screen? Testing the Purple Text: Now, let's take a look at the text formatted with a purple font. The color contrast test results show that using a purple font can be problematic for your readers in just about any screen display mode. Accommodating Everyone When Emphasizing TextSometimes it is necessary to use color to emphasize things when creating digital teaching and learning resources (or any digital text resources). For instance, differentiating between items based on their color may be a functional technical requirement (such as with colored buttons), or one of your required content learning outcomes (such as differently colored safety labels). In those cases, you can use the following strategies:

The key is to ensure that any emphasis you intend to create by using color is not lost for any readers who cannot actually perceive that color, or who will have difficulty viewing the text because of the color choice! Additional Resources

ReferencesOpenDyslexis (n.d.). OpenDyslexic: A typeface for Dyslexia. https://opendyslexic.org/

Power, R. (2020, February 13). Helping Everyone Access Your Online Teaching Resources. [Web log post]. Power Learning Solutions. https://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/blog/helping-everyone-access-your-online-learning-resources Power, R. (2023, April 6). A Picture Isn't Always Worth a Thousand Words... [Web log post]. Power Learning Solutions. https://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/blog/a-picture-isnt-always-worth-a-thousand-words Power, R. (2023). Chapter 17. Accessibility in Online Learning. Everyday Instructional Design: A Practical Resource for Educators and Instructional Designers. Power Learning Solutions. https://pressbooks.pub/everydayid/chapter/accessibility-in-online-learning/ TPGI (2024). Colour Contrast Analyzer (CCA). https://www.tpgi.com/color-contrast-checker/ World Wide Web Consortium (2023). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2. https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG22/

0 Comments

Sometimes we share videos with our students that are not narrated, and that contain just on-screen text. While viewers can technically read the text embedded in the video, this method does not truly meet Digital Accessibility requirements. That's because the use of embedded text in a video is the same as embedding text within an image in a document. It is not machine-readable, and thus it excludes audience members who may need to use a screen reader application for any reason (they may be visually-impaired, have low language reading ability, have a reading-related learning disability such as Dyslexia, or they may be a non-native language speaker who needs to translate your text for better comprehension). The two best ways to help all potential viewers get the most out of your non-narrated video content are to:

Creating Captions In YouTubeYouTube Creators (2021) has an excellent overview of how to add or edit captions either when you are uploading your video, or after your video has already been published. Remember, for a video with no narration (just text on screen), you will need to transcribe that text into the captions editor (either manually, or copy-paste the "slide" text from your video, and insert it to align with the timings when it appears on screen. Creating Your Own Captions FileAnother option for creating subtitles or captions for a non-narrated video is to use an external video editing application, like Screencast-O-Matic (2019). This option works well if you have a copy of the video file (MP4 or other format) on your computer, but is less useful if you use a tool like PowToon (2022) to create your video and export it directly to YouTube (because you cannot download the video file unless you have a pro-level subscription). While the following webinar demonstration video (Power, 2021, April 9) features the creation of captions for a narrated video using Screencast-O-Matic, the steps for creating, editing, and uploading your captions file to YouTube would be the same for a text-only video. Adding a Transcript FileIn addition to making sure your text-only video has Closed Captions enabled, I also strongly recommend adding a transcript file for your visually-impaired users. A transcript file can be opened or downloaded. Your audience members can then use any screen reader application (such as JAWS (Freedom Scientific, n.d.), NVDA (NV Access, 2023), or Google Read and Write (Texthelp, 2023)) to read the on-screen video text out load to them. The following video shows how I uploaded a transcript file to Google Drive, and then added a link to that transcript to the video description for my instructor welcome video in YouTube. Remember to make sure your transcript file meets basic document accessibility requirements before sharing it! For more on that topic, refer to my blog post Helping Everyone Access Your Online Learning Resources (Power, 2020). ReferencesFreedom Scientific. (n.d.). JAWS. [computer software]. https://www.freedomscientific.com/

NV Access (2023). About NVDA. [computer software]. https://www.nvaccess.org/about-nvda/ Power, R. (2019, November 9). Hi There! Meet Rob Power. [video]. https://youtu.be/ff-6GtdX9xM Power, R. (2020, February 13). Helping Everyone Access Your Online Learning Resources. [Web log post]. Power Learning Solutions. https://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/blog/helping-everyone-access-your-online-learning-resources Power, R. (2021, April 9). Creating Your Own Video Captions (Webinar Demonstration). [video]. https://youtu.be/4ghNMjCDOfg Power, R. (2023, May 1). Adding Transcripts to YouTube Videos. [video]. https://youtu.be/q5z_ZHCVFjg PowToon (2022). https://www.powtoon.com/ Screencast-O-Matic (2019). Video Creation for Everyone. [Web page]. https://screencast-o-matic.com/ Texthelp (2023). Read&Write for Google Chrome. [computer software]. https://www.texthelp.com/products/read-and-write-education/for-google-chrome/ YouTube Creators (2021, May 5). How to Add Captions While Uploading & Editing Your Videos. [video]. https://youtu.be/rB9ql0L0cU Sometimes Using Graphics Does More Harm Than Good

Does the Graphic Contain Text?There are lots of cases where the graphics we use contain text. Sometimes it is unavoidable. The questions you should be asking in this case are:

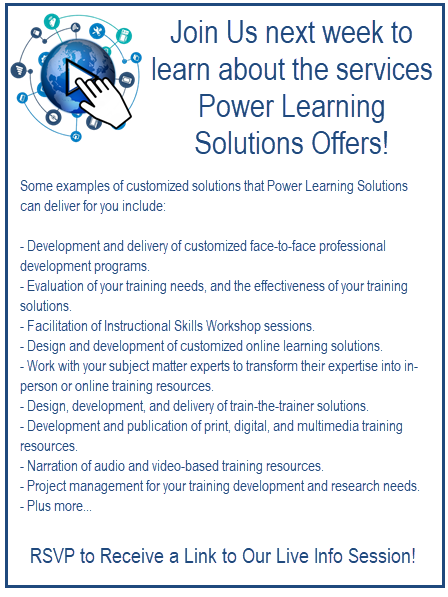

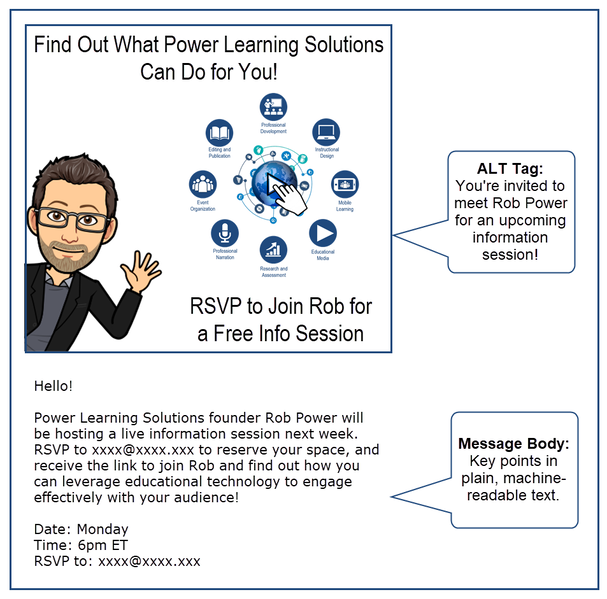

The following graphic illustrates a common example of graphics that I see in my email inbox where actual text should be used instead of the image: There is nothing in this graphic that could not be put in regular text format, and a screen reader cannot "see" the text in the image to read it out to you. Sure, you could repeat the text within the ALT tag for the image, so that a screen reader will read it out... but what's the point? The graphic does not actually clarify or add anything to the message, and you are wasting time creating the graphic and typing the text into the ALT tag when you could simply type it right onto the page! Additionally, text within your image will NOT reflow and resize based on the reader's screen size and orientation, which could also render that text unreadable to your entire audience. You are also preventing anyone who uses an Accessibility plugin from modifying the font, color, or contrast of the text to make it more readable in their specific context. And, besides the message potentially being lost for anyone using a screen reader (if they do engage with the content at all), there is the potential that your intended audience may also view the message as SPAM, and thus ignore it! Here is a better example of a graphic that could be used to accompany the same message. In this case, you can see that the image is being used to draw visual readers' attention to some key points. The accompanying ALT text tells a screen reader user why the image is being used. And the main points of the message are included in regular text format in the body of the page. When The Message Gets Washed AwayIf you are going to use a graphic as part of your message or content page, make sure you test that image in "dark mode." Most of the time, we are not working in dark mode when we create graphics. If our graphics have transparent backgrounds, they will display differently for any reader who has adjusted the color scheme of their screen. Parts of the graphic may end up getting "washed out" by a different color screen background, rendering them unreadable. Here is an example of an email message that contains a graphic with a transparent background, as viewed in dark mode on my mobile device. The message was unreadable until I got to my desktop computer! The quick fix to this is to remove the transparent background before publishing the graphic, and choose a background color that has a sufficient color contrast ratio with the foreground (text). TL:DR

I recently ran into an issue during a Microsoft Teams meeting, and did some digging afterwards to troubleshoot. The problem was that I could not hear any sound through my wireless headset during the meeting, while using a custom audio configuration that had previously worked flawlessly (a Logitech USB webcam, Blue Snowball external microphone, and a SkullCandy Hesh 2 Bluetooth headset). It seems that Microsoft has made some changes to both Teams and Windows that now prevent anyone from using both a Bluetooth headset and an external microphone during Teams meetings. Windows detects a Bluetooth headset with a built-in microphone as telephone device – which means that Teams will want to use it as an all-in-one device and will prevent you from hearing sound once you turn on your external microphone. Previously, you were able to prevent this by turning off the “telephony” service for your headset (under the device properties) – but Microsoft has now removed the ability to access that tab and turn off that service in the latest builds of Windows 11. I played around with my system, and determined that this issue does not impact other online meeting platforms such as Zoom, Google Meet, or Skype – just Teams. TLDR: If you encounter an issue with not being able to hear sound during a Teams meeting, it may be that you are trying to use a wireless headset and an external microphone at the same time – and you are no longer able to do that!

As many post-secondary institutions prepare to return to in-person classes following the switch to remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, we're all wondering how we can effectively return to classroom teaching with social distancing practices in place. If there's one thing that we've learned from the shift to online teaching and learning, it's that there are a number of digital tools that we can use to share resources and maximize student engagement during virtual classes. Well, the good news is that many of those tools and approaches can also be leveraged in the classroom.

In preparation for a return to in-person classes at Cape Breton University, my colleagues and I took some time to visit one of our campus' large lecture theatres to record some demonstrations of how we can leverage digital tools, including Microsoft Teams, to engage with our students safely and effectively. The following are a series of videos that I edited from that demonstration session. In these videos, we cover how to:

Additional Resources

Resources Referenced in Demonstrations

Microsoft Teams

Access the complete video library of Microsoft Teams Tips and Tricks for Educators at https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIJ8QfsveW2Zp0ksxQAoBMqZkRvTyF1pa

Moodle

Access the complete library of Moodle Tips and Tricks for Educators at https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIJ8QfsveW2Zbm4pm-W6rtdI_vj4gnDMM Update (April 17, 2020) -- this post has been updated with a new video demonstrating how to create your own YouTube channel for sharing instructional videos with your students.  I recently had a question which reminded me... I should never assume that everyone already knows how to use YouTube! I like YouTube as a EdTech tool, because it is a powerful way to share video content with your students (why bother worrying about how to process and stream video content, when YouTube already has powerful servers that will do it for you!). And that doesn't mean that you have to direct them to YouTube to view it. You can embed your YouTube videos directly into a website, or an LMS content page. Adding Video to YouTubeTo that end, here are a few resources that might be helpful. This first video shows the basics of how to upload and share videos in YouTube. As noted in the video... you do need to login. All you need for that is a GMail / Google account! Choosing a Privacy SettingThis next video goes over some of the basics of choosing a privacy setting for your video. It's important to choose the right setting. If you want your video to be available publicly, then choose "Public." If you want to share your video with your students, and embed it into a webpage or LMS page, choose "Unlisted." "Unlisted" means the video can't be found using a search engine, but anyone with the link can still view it without a password. If you don't want anyone to view it without you directly allowing "just that person" to see it, choose "Private." Even with a direct URL, no one will be able to watch the video unless you authorize their email address! Embedding Video in Your LMSFinally... here are some quick tutorial videos showing the basics of how to embed a YouTube video (whether it's one you uploaded, or another video that you found on YouTube) into pages in some of the LMS platforms that I have worked with most frequently:

Copyright NoteOne of the great things about embedding a YouTube video into a webpage or course page in an LMS is that you won't be violating the video owner's copyright (assuming the person who posted the video isn't violating a copyright within the video itself!). That's because you're not actually making a copy of the video. You're essentially just sharing a link to it, and if the owner decides they don't want anyone to use it anymore, they can remove the video, or change the privacy setting. When they do that, your embedded player simply won't show it any more! Choosing a Copyright Licence When Posting Your Video to YouTubeYouTube has a few different "licencing" options when you post your own videos. The default is "Standard YouTube Licence," which is essentially a copyright licence. I prefer to change that setting to a Creative Commons Attribution. Using a CC Attribution means that you are letting others reuse your video as an Open Access resource, so long as they properly attribute you. It also means that you are allowing others to make a copy, edit, remix, or combine parts of your video with other Creative Commons videos from YouTube! Creating Your Own YouTube ChannelIf you have a Google or GMail account, then you already have a YouTube account. In this video, I demonstrate the basic steps to setting up your own YouTube channel for sharing instructional videos with your students. Time Limits on YouTube Videos By default, new YouTube accounts have a time limit of 15 minutes for each video upload. To increase this, you will need to "verify" your account with Google. Instructions on how to do this can be found HERE. ReferencesEves, D. (2014, January 2). How to Properly Upload Videos to YouTube. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/Hlxqk0iHp5w

Gniffke, D. (2016, May 11). Canvas - Embedding Video. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/l2ebbdJPy0o Google (2020). Upload videos longer than 15 minutes. [Web page]. YouTube Help. Available from https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/71673?co=GENIE.Platform%3DDesktop&hl=en&oco=0 Interesting Videos (2017, February 2). Creative Commons License YouTube cc Not Standard Youtube License. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/e-46x3mpS8M Power, R. (2015, January 25). Embedding Videos in D2L. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/QZ4558qvzhw Power, R. (2020, April 17). Creating a YouTube Channel for Educators. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/Uy_5gOV80LY Scott Gardiner Technical Services (2016, May 2). How to Embed a YouTube Video on Your Weebly Website. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/4PfKoV9XyN0 Straub, S. (2018, February 17). How To Embed Media Such As Youtube Videos Into Blackboard. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/BWIF_d2Vcc4 Tattershall, E. (2017, June 6). Embedding Video in Your Moodle Course. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/K4zAZuHGNrM thebasicgist (2013, June 6). Youtube Settings: Unlisted v Private v Public. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/fViYcDDZyhk University of Leicester Learning and Teaching (2016, February 29). Embed a YouTube video in Blackboard. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/ES-CZtBdHOI

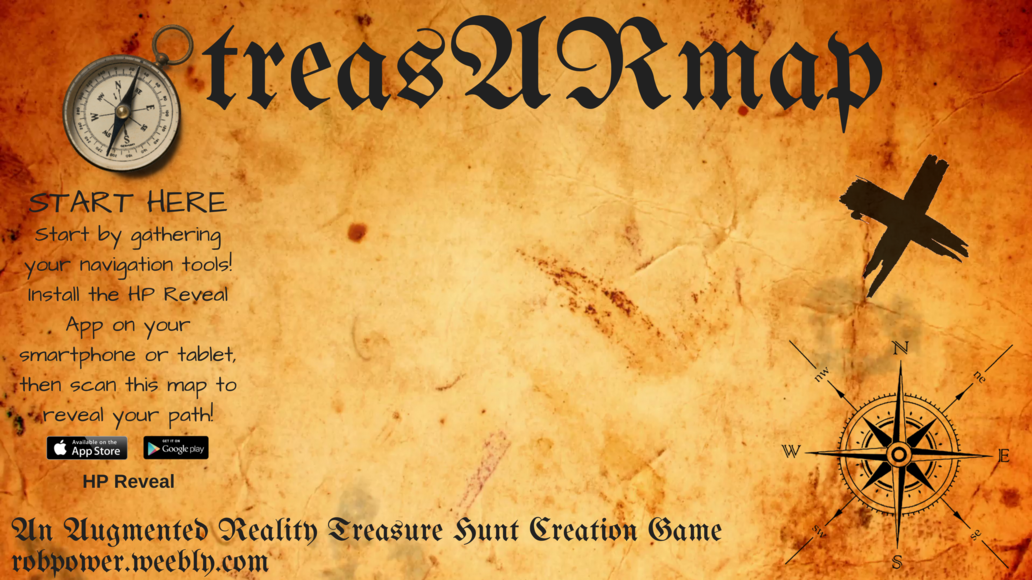

I've been playing around a bit with using HP Reveal Studio (formerly Aurasma Studio) to created Augmented Reality resources, such as interactive game boards and conference posters. For Mobile Summit 2018 and the 17th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning (mLearn 2018), I developed a workshop on how to use HP Reveal Studio to create an AR treasARmap. That's a magic treasure map that appears blank for my students, until they scan it using the HP Reveal (formerly Aurasma) app using their mobile devices. What they see when they scan the blank map is something like the image below, where the pieces of the map slowly reveal themselves.

The QR code and URL on the image above will take you to the companion resources that I created for the workshops. But, since I've had a lot of requests for this, I've put together this blog post to bring everything together into one spot, and show how I created the AR treasARmap.

About treasARmap

The treasARmap map was created using the Canva free online poster and infographic creation suite. It was then "augmented" using a free HP Reveal Studio account. This is what the final product looks like:

Accessing the Hidden Treasure Map

To access this augmented reality "treasARmap," install the HP Reveal (formerly Aurasma) AR app on your mobile device. Launch the app, point your device at the image below, and click on the AR objects to follow a team's path to the finish line!

Get the App

Follow Rob Power, EdD on HP Reveal

Step 1: Making a treasARmap Poster

Do It Yourself

Additional Useful Tutorials

Step 2: Augmenting Your treasARmap

Do It Yourself

Additional Useful Tutorials

Share Your treasARmap

I'd love to see what you come up with playing around with the concept of creating AR treasARmaps, or other AR resources for your teaching and learning! I've set up the following Padlet wall as a spot where participants in the treasARhunt workshops can share their completed projects... but feel free to post yours, as well. (Just be sure to include a note as to "who" we need to follow using the HP Reveal app to bring your treasARmap to life!)

The benefits and drawbacks of the integration of technology into both the curriculum, and teaching and learning practice, continue to be contentious issues on multiple fronts. On the one hand, there are those who continue to subscribe to Clark’s (1994 a, b) contention that technology has no impact whatsoever on learning achievement. Evidence may point to this conclusion that technology integration results in no significant difference in learning achievement compared to “traditional” classroom settings. However, there are many more reasons why it is imperative that teachers and schools thoughtfully plan for meaningful technology integration. Clark’s long-time rival in the media effectiveness debate, Kozma (1994 a, b), points to the fact that newer technologies enable pedagogical approaches and learning experiences that previously were not possible (and for which there can be no technology-free learning achievement comparison). These learning opportunities include the ability for remote learners, and those facing accessibility challenges, to be engaged on unprecedented levels. Another imperative for meaningful technology integration is the preparation of learners to be responsible digital citizens, who are empowered to leverage technology to meet emerging needs in their lives, learning, work, and society. About the eBook Technology and the Curriculum: Summer 2018 has been written by participants in EDUC 5303G, a course in the Masters of Education program at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology. The mandate of EDUC 5303G is to [examine] the theoretical foundations and practical questions concerning the educational use of technology. The main areas of focus… include learning theory and the use of technology, analysis of the learner, curriculum, and technology tools, leading-edge technology programs/initiatives, implementation, assessment, and barriers toward using technology. The overall focus of the course is on developing a critical, evidence-based, theoretically grounded perspective regarding the use of technology in the curriculum (EDUC 5303G Course Syllabus, Spring/Summer 2018). Each chapter in the eBook focuses was written by a course participant, and focuses on a topic chosen by them that stems from the issues explored throughout the Spring/Summer 2018 term. The authors first submitted their chapter drafts for feedback from the instructor. Each chapter also underwent a double-blind peer-review process, before the final versions were added to the actual eBook in Pressbooks. Why an Open Access eBook EDUC 5303G aims to live up to its own mandate, and meaningfully integrate technology into the course curriculum, and overall learning experience. Digital communications tools, such as the Pressbooks platform, allow for a transformation of the traditional academic paper writing experience. Rather than writing a paper to demonstrate topic understanding, and competence with writing mechanics, for just an instructor’s review, technology enables course participants to write with purpose. This eBook chapter writing endeavour allows participants in a course like EDUC 5303G to more fully engage with their peers in the writing process, in a manner that reflects the realities of academic writing beyond the classroom. The project also allows them to share their work with a global audience. This integration of technology forces students to take deeper ownership of their work, but also allows them to share the fruits of their labours with others who could benefit from their explorations of topics related to the meaningful use of technology in education. It gives me great pleasure to facilitate access to the tools and processes used by provide the EDUC 5303G Spring/Summer 2018 participants to produce the eBook, and to share the resources they have compiled. ReferencesClark, R.E. (1994a). Media will never influence learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 42(2), pp. 21-30.

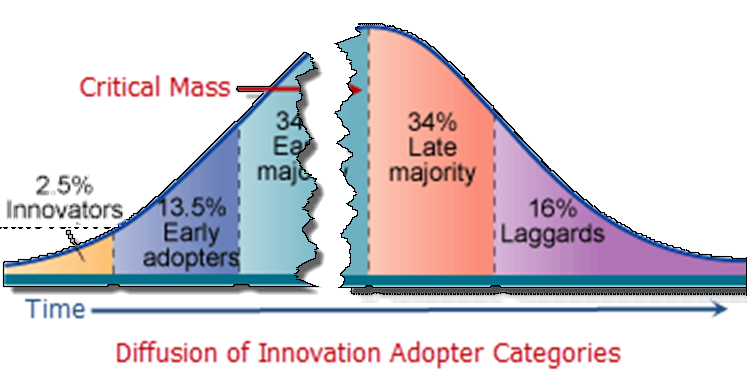

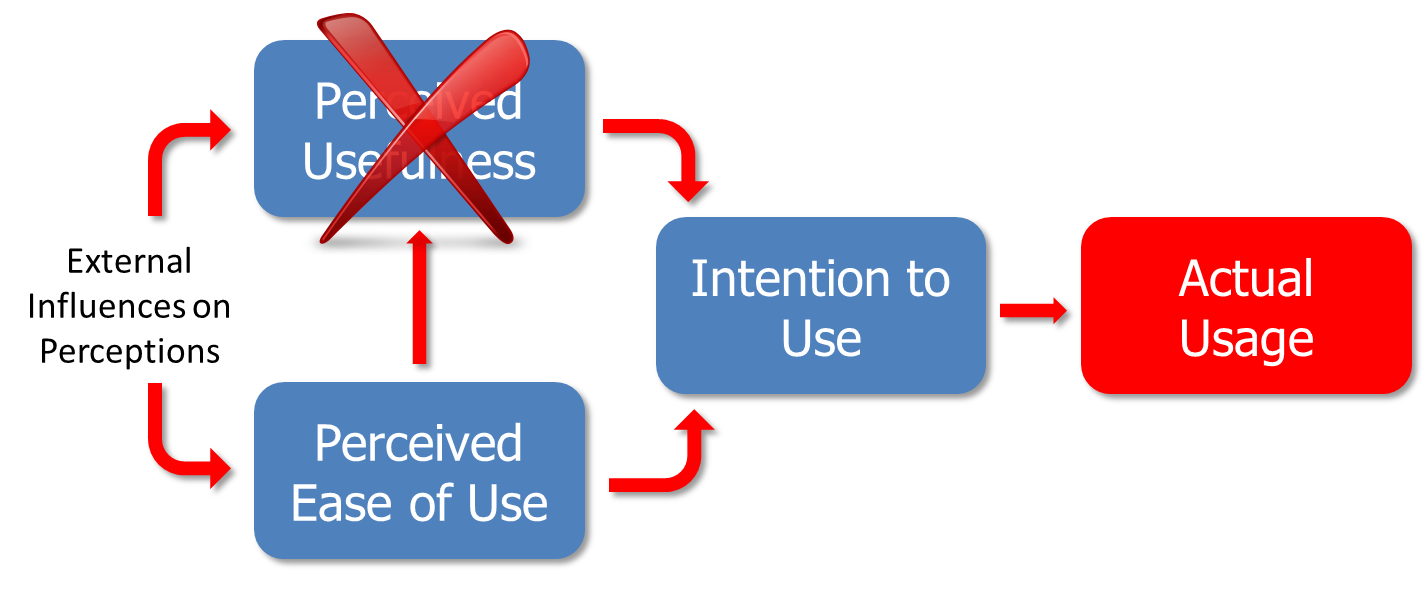

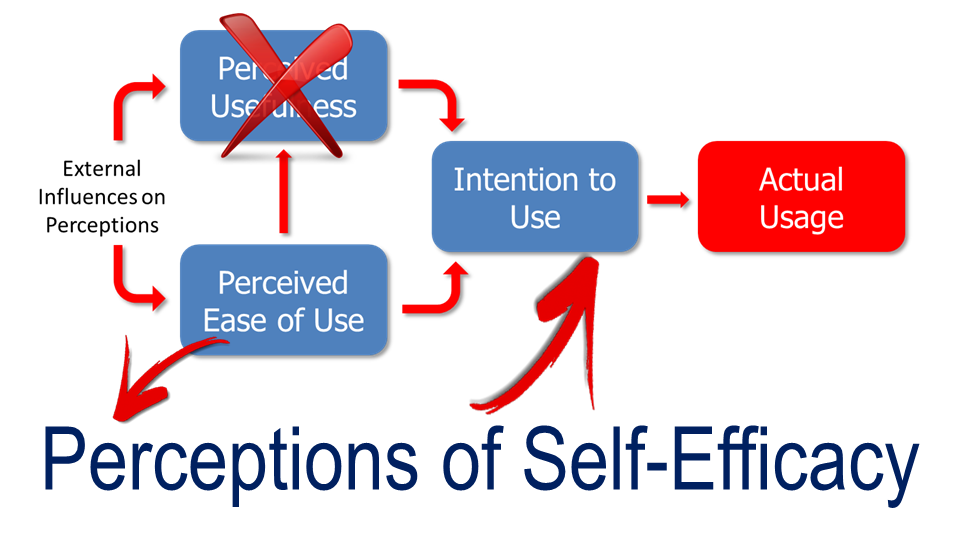

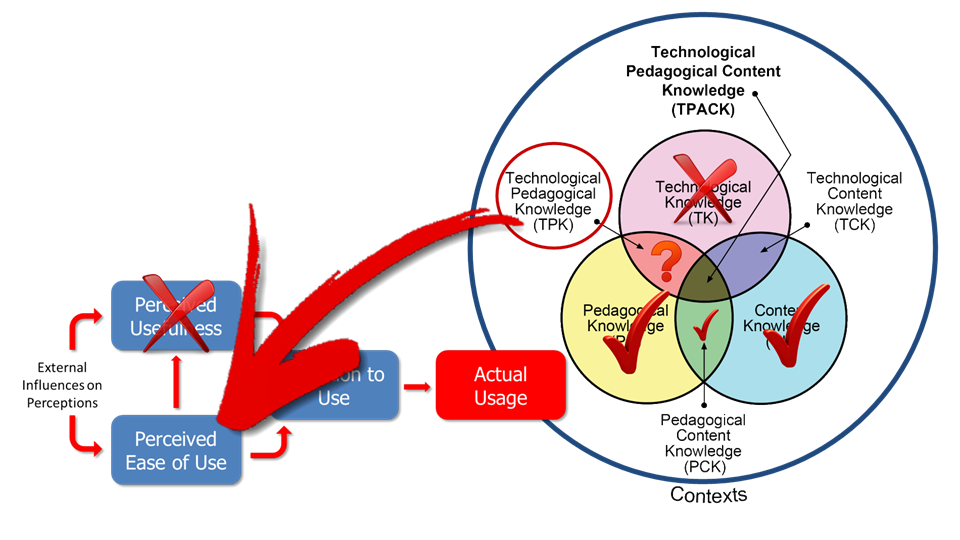

Clark, R.E. (1994b). Media and method. Educational Technology Research and Development, 42(3), 7-10. Kozma, R. (1994a). Will media influence learning? Reframing the debate. Educational Technology Research and Development, 42(2), pp. 7 - 19. Kozma, R. (1994b). A reply: Media and methods. (1994). Educational Technology Research and Development, 42(3), pp. 11 - 14. Power, R. (Ed). (2018). Technology and the Curriculum: Summer 2018. [eBook]. Surrey, BC, Canada: Power Learning Solutions. Available from https://techandcurriculum.pressbooks.com/ What are the challenges that we face as technology integration specialists in our teaching and learning contexts? And, what tips or advice do you have for overcoming some of those hurdles? Those are questions that I just posed to graduate education students participating in my Spring/Summer 2018 section of EDUC5303G: Technology and the Curriculum. From my experience (and from my chapter in Yu, Ally and Tsanikos (2018) and my keynote presentation at Mobile Summit 2018)... One of the biggest hurdles that we seem to face is getting past shifting into the "Early Adopters" or very early "Early Majority" phases of the Diffusion of Innovation model (Rogers, 1974): If we look at the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989), I don't think that the problem with intention (and action) to integrate technology lies with "Perceptions of Usefulness." We see examples every day of how useful different technologies can be. Digital technologies can do just about anything that we can dream up for them to do... and examples of innovative EdTech use abound. It's easy to find them, and it's easy to share them. (That doesn't mean we should slack off on our efforts in this area... ideas and inspiration are still of vital importance.) So... if the problem is not with "Perceptions of Usefulness" in TAM, it must be with "Perceived Ease of Use." It's pretty reasonable to understand the causes of this problem. Ally and Tsinakos (2014) lament that our teacher preparation programs are largely still preparing teachers to function in a system that hasn't really existed since the 1980s. Finger, Jamieson-Proctor and Albion have similarly lamented that changes in digital technologies that could benefit the curriculum: "have not always translated into practice which has resulted in a focus on the need for improvements in pre-service teacher education programs and professional development of practising teachers” (2010, p. 114) The Self-Confidence ProblemThe biggest problem we face in getting teachers to integrate technology into their practice isn't that they don't see it as useful... it's that they don't feel comfortable using it. They lack a strong perception of self-efficacy. As Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) note: Perceptions of self-efficacy can influence a teacher’s “levels of planning and organization” and “willingness to experiment with new methods to meet the needs… of students” (p. 783). If we can help teachers to feel more comfortable with using technology, and they already see that technology as being potentially useful, they'll be more likely to experiment with it in their teaching and learning practice. So... how do we get there? Filling the Gaps in TPACKIn my Handbook chapter, and Mobile Summit 2018 Keynote, I focused in on how widespread TPACK (Koehler & Mishra, 2006, 2008; TPACK.org, 2012) has become in guiding teacher professional development when it comes to technology integration. As teachers, we already have strengths in the areas of Content Knowledge and Pedagogical Knowledge. It's easy for us to demonstrate the usefulness of different technologies, and to find training or resources on the technical how-to of technologies that we do choose to integrate (assuming that we can find the time to pursue them!). So we've got those aspects of TPACK covered off pretty well. And, if we're using TPACK to help shape professional development based on our needs as teachers, then we don't need to focus so much on addressing those areas. But, what TPACK shows us we're still missing, and fails in-and-of-itself to deliver, is the actual Technical-Pedagogical Knowledge area. Without this understanding of pedagogical decision-making for the use of technology, how are teachers going to increase their confidence in their ability to use technology effectively? Focusing on Good PedagogyAs I've already noted, teachers are pedagogical professionals. If we want to increase their self-efficacy when it comes to meaningfully and effectively integrating technology into their practice, we don't need to focus on either the usefulness of the technology, or how to use specific tech tools or "apps du-jour." What we need to focus on is how to make pedagogical decisions first, decide when tools are needed, and then find appropriate tools to "get the job done." In my research, I've demonstrated exactly what Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) were talking about. When provided with tools to support pedagogical decisions around the use of technology, teachers became both more interested in, and more willing to experiment with technologies they hadn't used before. In my research, I focused on the use of mobile learning strategies, and I provided teachers with professional development that focused on making instructional design decisions using an evidence-driven framework. They did get to the "fun" bit of playing with the tech itself (I mean, how boring would PD be if we never got a chance to play with the toys!) -- but I carefully minimized the cognitive load of learning new technologies, so that the teachers could focus on the technology integration decisions that they were making. The Key Takeaway: Purpose and PedagogyWhat's the point of my rant in this blog post? While we should keep up with experimenting with innovative technology use in education, our main concern should not be with either what the technology can possibly do, or how to use that technology. The focus should be on how to use the technology meaningfully. To get there, we need to place sufficient focus in teacher preparation programs and professional development efforts on how to make decisions about when it's appropriate to use technology tools, and how to frame our instructional design decisions. If teachers feel confident as to why they are using tools, and in the fact that it's not so important that they be experts with all of the tools themselves (after all -- our students can oftentimes provide us with on-the-spot tech support!), then their self-efficacy will go up. That will get more teachers to the "Intention to Use" stage in TAM, which will bring us closer to the Late Majority stage in the Diffusiion of Innovation model. You can find my full slidedeck from my Mobile Summit 2018 keynote presentation HERE. You can learn more about my research into the CSAM framework HERE, and the mTSES tool that I used to measure changes in teachers' perceptions of self-efficacy with mobile learning HERE. ReferencesAlly, M., & Tsinakos, A. (2014). Increasing access through mobile learning. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Athabasca University Press and the Commonwealth of Learning. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=466

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. doi:10.2307/249008 Finger, G., Jamieson-Proctor, R., Albion, P. (2010). Beyond pedagogical content knowledge: The importance of TPACK for informing preservice teacher education in Australia. In M. Turcanyis-Szabo & N. Reynolds (Eds.), Key competencies in the knowledge society (pp. 114-125). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 109(6), 1017-1054. Retrieved from http://punya.educ.msu.edu/publications/journal_articles/mishra-koehler-tcr2006.pdf Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. In AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.), The handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators (pp. 3-29). American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education and Routledge, NY, New York. Power, R. (2018). The CSAM framework. [Web page]. Power Learning Solutions. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/csam.html Power, R. (2018, May 16). Making mobile learning work for educators and students. Opening keynote address at Mobile Summit 2018, 16-17 May 2018, Scarborough, ON, Canada. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/making-mobile-learning-work.html Power, R. (2018). The Mobile Teacher's Sense of Efficacy Scale (mTSES). [Web page]. Power Learning Solutions. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/mtses.html Power, R. (2018). Supporting mobile instructional design with CSAM. In S. Yu, M. Ally, & A. Tsanikos (Eds.), Mobile and ubiquitous learning: An international handbook, pp. 193-209. Singapore: Springer Nature. DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-6144-8_12. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6144-8_12 Rogers, E. (1974). New product adoption and diffusion. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(4), 290–301. tpack.org (2012). The TPACK image. Retrieved from http://www.tpck.org/ Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing and elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783-805. |

AuthorRob Power, EdD, is an Assistant Professor of Education, an instructional developer, and educational technology, mLearning, and open, blended, and distributed learning specialist. Recent PostsCategories

All

Archives

June 2024

Older Posts from the xPat_Letters Blog

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed