|

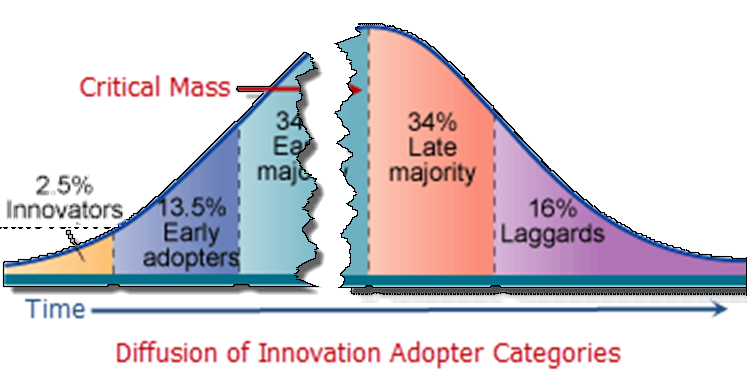

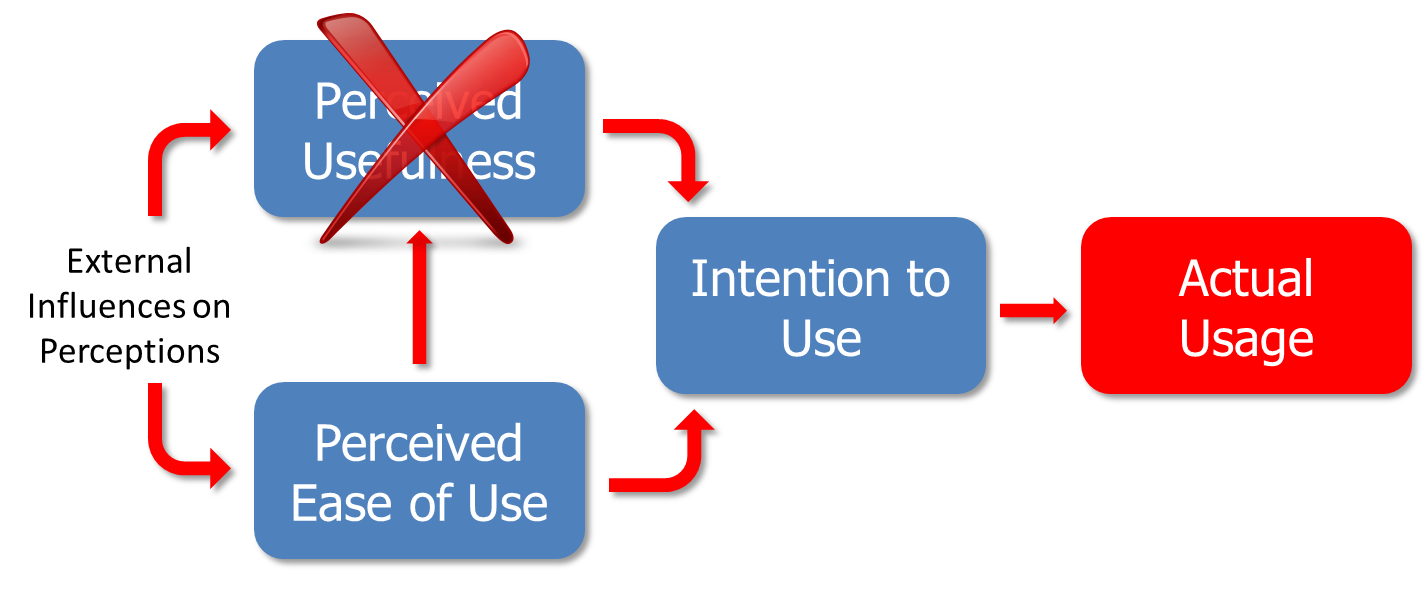

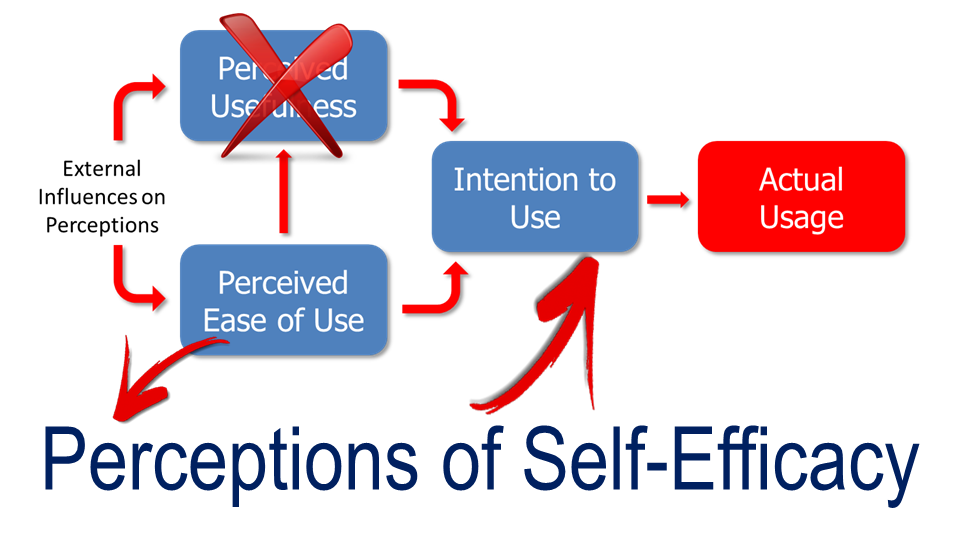

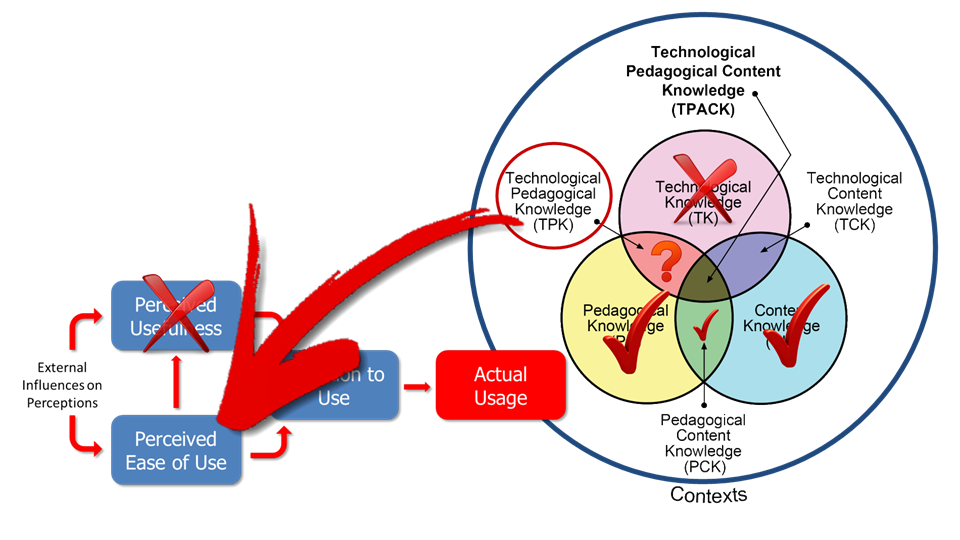

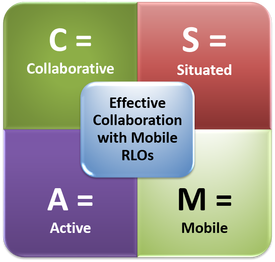

What are the challenges that we face as technology integration specialists in our teaching and learning contexts? And, what tips or advice do you have for overcoming some of those hurdles? Those are questions that I just posed to graduate education students participating in my Spring/Summer 2018 section of EDUC5303G: Technology and the Curriculum. From my experience (and from my chapter in Yu, Ally and Tsanikos (2018) and my keynote presentation at Mobile Summit 2018)... One of the biggest hurdles that we seem to face is getting past shifting into the "Early Adopters" or very early "Early Majority" phases of the Diffusion of Innovation model (Rogers, 1974): If we look at the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989), I don't think that the problem with intention (and action) to integrate technology lies with "Perceptions of Usefulness." We see examples every day of how useful different technologies can be. Digital technologies can do just about anything that we can dream up for them to do... and examples of innovative EdTech use abound. It's easy to find them, and it's easy to share them. (That doesn't mean we should slack off on our efforts in this area... ideas and inspiration are still of vital importance.) So... if the problem is not with "Perceptions of Usefulness" in TAM, it must be with "Perceived Ease of Use." It's pretty reasonable to understand the causes of this problem. Ally and Tsinakos (2014) lament that our teacher preparation programs are largely still preparing teachers to function in a system that hasn't really existed since the 1980s. Finger, Jamieson-Proctor and Albion have similarly lamented that changes in digital technologies that could benefit the curriculum: "have not always translated into practice which has resulted in a focus on the need for improvements in pre-service teacher education programs and professional development of practising teachers” (2010, p. 114) The Self-Confidence ProblemThe biggest problem we face in getting teachers to integrate technology into their practice isn't that they don't see it as useful... it's that they don't feel comfortable using it. They lack a strong perception of self-efficacy. As Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) note: Perceptions of self-efficacy can influence a teacher’s “levels of planning and organization” and “willingness to experiment with new methods to meet the needs… of students” (p. 783). If we can help teachers to feel more comfortable with using technology, and they already see that technology as being potentially useful, they'll be more likely to experiment with it in their teaching and learning practice. So... how do we get there? Filling the Gaps in TPACKIn my Handbook chapter, and Mobile Summit 2018 Keynote, I focused in on how widespread TPACK (Koehler & Mishra, 2006, 2008; TPACK.org, 2012) has become in guiding teacher professional development when it comes to technology integration. As teachers, we already have strengths in the areas of Content Knowledge and Pedagogical Knowledge. It's easy for us to demonstrate the usefulness of different technologies, and to find training or resources on the technical how-to of technologies that we do choose to integrate (assuming that we can find the time to pursue them!). So we've got those aspects of TPACK covered off pretty well. And, if we're using TPACK to help shape professional development based on our needs as teachers, then we don't need to focus so much on addressing those areas. But, what TPACK shows us we're still missing, and fails in-and-of-itself to deliver, is the actual Technical-Pedagogical Knowledge area. Without this understanding of pedagogical decision-making for the use of technology, how are teachers going to increase their confidence in their ability to use technology effectively? Focusing on Good PedagogyAs I've already noted, teachers are pedagogical professionals. If we want to increase their self-efficacy when it comes to meaningfully and effectively integrating technology into their practice, we don't need to focus on either the usefulness of the technology, or how to use specific tech tools or "apps du-jour." What we need to focus on is how to make pedagogical decisions first, decide when tools are needed, and then find appropriate tools to "get the job done." In my research, I've demonstrated exactly what Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) were talking about. When provided with tools to support pedagogical decisions around the use of technology, teachers became both more interested in, and more willing to experiment with technologies they hadn't used before. In my research, I focused on the use of mobile learning strategies, and I provided teachers with professional development that focused on making instructional design decisions using an evidence-driven framework. They did get to the "fun" bit of playing with the tech itself (I mean, how boring would PD be if we never got a chance to play with the toys!) -- but I carefully minimized the cognitive load of learning new technologies, so that the teachers could focus on the technology integration decisions that they were making. The Key Takeaway: Purpose and PedagogyWhat's the point of my rant in this blog post? While we should keep up with experimenting with innovative technology use in education, our main concern should not be with either what the technology can possibly do, or how to use that technology. The focus should be on how to use the technology meaningfully. To get there, we need to place sufficient focus in teacher preparation programs and professional development efforts on how to make decisions about when it's appropriate to use technology tools, and how to frame our instructional design decisions. If teachers feel confident as to why they are using tools, and in the fact that it's not so important that they be experts with all of the tools themselves (after all -- our students can oftentimes provide us with on-the-spot tech support!), then their self-efficacy will go up. That will get more teachers to the "Intention to Use" stage in TAM, which will bring us closer to the Late Majority stage in the Diffusiion of Innovation model. You can find my full slidedeck from my Mobile Summit 2018 keynote presentation HERE. You can learn more about my research into the CSAM framework HERE, and the mTSES tool that I used to measure changes in teachers' perceptions of self-efficacy with mobile learning HERE. ReferencesAlly, M., & Tsinakos, A. (2014). Increasing access through mobile learning. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Athabasca University Press and the Commonwealth of Learning. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=466

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340. doi:10.2307/249008 Finger, G., Jamieson-Proctor, R., Albion, P. (2010). Beyond pedagogical content knowledge: The importance of TPACK for informing preservice teacher education in Australia. In M. Turcanyis-Szabo & N. Reynolds (Eds.), Key competencies in the knowledge society (pp. 114-125). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 109(6), 1017-1054. Retrieved from http://punya.educ.msu.edu/publications/journal_articles/mishra-koehler-tcr2006.pdf Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. In AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.), The handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators (pp. 3-29). American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education and Routledge, NY, New York. Power, R. (2018). The CSAM framework. [Web page]. Power Learning Solutions. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/csam.html Power, R. (2018, May 16). Making mobile learning work for educators and students. Opening keynote address at Mobile Summit 2018, 16-17 May 2018, Scarborough, ON, Canada. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/making-mobile-learning-work.html Power, R. (2018). The Mobile Teacher's Sense of Efficacy Scale (mTSES). [Web page]. Power Learning Solutions. Available from http://www.powerlearningsolutions.com/mtses.html Power, R. (2018). Supporting mobile instructional design with CSAM. In S. Yu, M. Ally, & A. Tsanikos (Eds.), Mobile and ubiquitous learning: An international handbook, pp. 193-209. Singapore: Springer Nature. DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-6144-8_12. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6144-8_12 Rogers, E. (1974). New product adoption and diffusion. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(4), 290–301. tpack.org (2012). The TPACK image. Retrieved from http://www.tpck.org/ Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing and elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783-805.

1 Comment

My first encounter with designing for Digital Accessibility was through a professional development program offered to my colleagues and me in the Advanced Learning Technologies Centre at College of the North Atlantic-Qatar by the Mada Assistive Technology Centre. I've been including discussions of digital accessibility in my graduate and undergraduate-level educational technology courses for several years now. I've also been "preaching" about the need to think about digital accessibility when designing eLearning courses and resources to my colleagues in various sectors. To further our ability to meet this need, in February 2017, I and my teammates in the Fraser Health Authority Online Learning Team participated in an online MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) through the University of Southampton called Digital Accessibility: Enabling Participation in the Information Society. Recently, I've received a number of requests for more information and resources -- both from my students, and my colleagues. I'm also working on a couple of new courses, where I'll be discussing this topic again. So, I figured that I would compile some of my favorites from several courses I've taught into a single blog post on the Power Learning Blog site. This post is by no means comprehensive, and I highly encourage you to search out the legislation, guidelines, and toolkits for your own province, state, or region... but these are solid resources that will help you understand the importance of addressing digital accessibility for online teaching and learning. I'll start with this excellent video by Berman (2014), who does a great job of showing us why we should care about Digital Accessibility: Web Accessibility Matters Traxler (2016). talks about accessibility and inclusion of all learners in the context of increased use of mobile technologies to mediate learning experiences.

Accessibility Toolkits for Online Teaching and LearningMany jurisdictions have already mandated technical and instructional design standards for user accessibility. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). provides an overview of accessibility issues and a list of standards that are increasingly drawn upon as the foundations of the accessibility policies, standards, and legislation being adopted by many organizations and jurisdictions. A common theme emerging from discussions of accessibility standards is that designing with accessibility in mind improves the learning experience for everyone – not just learners with specific accessibility issues.

Canadian Provincial Standards and Resources In Ontario, Accessibility in teaching and learning, including in online and blended learning contexts, is governed by the standards set out in the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act. (AODA). The Council of Ontario Universities provides a number of excellent resources to help you make your online teaching and learning resources are accessible to all learners, and AODA compliant:  Other Canadian provinces are quickly catching up with the benchmarks set out by the AODA. In British Columbia, digital accessibility for online teaching and learning will be governed by the BC Accessibility 2024 .guidelines. BCampus recently published an Open Access eBook on how to make digital learning resources, such as eBooks, compliant with digital accessibility guidelines: More Resources

ReferencesAccessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (2005, S.O. 2005, c. 11). Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/05a11

Berman, D. (2014, May 13). Web Accessibility Matters: Why Should We Care. [YouTube video]. Available from https://youtu.be/VIRx3RJzbZg College of the North Atlantic-Qatar (2018). [Web site]. Available from https://www.cna-qatar.com/ Coolidge, A., Doner, S., & Robertson, T. (2015). BCampus Open Education Accessibility Toolkit. [eBook]. Victoria, BC, Canada: BCampus. Available from https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/ Council of Ontario Universities (2017a). Accessible Digital Documents & Websites. [Web page]. Accessible Campus. Available from http://www.accessiblecampus.ca/reference-library/accessible-digital-documents-websites/ (Links to an external site.) Council of Ontario Universities (2017b). Accessibility in E-Learning. [Web page]. Accessible Campus. Available from http://www.accessiblecampus.ca/tools-resources/educators-tool-kit/course-planning/accessibility-in-e-learning/ Described and Captioned Media Program (2018). Caption It Yourself. [Web page]. Available from https://dcmp.org/learn/213 Fraser Health (2018). [Website]. Available from https://www.fraserhealth.ca/ FutureLearn (n.d.). Digital Accessibility: Enabling Participation in the Information Society. [Massive Open Online Course]. Available from https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/digital-accessibility Interaction Design Foundation (2018). Web Fonts are Critical to the Online User Experience - Don’t Hurt Your Reader’s Eyes. [Web page]. Available from https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/web-fonts-are-critical-to-the-online-user-experience-don-t-hurt-your-reader-s-eyes The Paciello Group (n.d.). Colour Contrast Analyzer (CCA). [Web page]. Available from https://developer.paciellogroup.com/resources/contrastanalyser/ Mada (2017). Mada Assistive Technology Centre. [Web page]. Available from https://mada.org.qa/en/Pages/default.aspx Province of British Columbia (2014). Accessibility 2024: Making B.C. the most progressive province in Canada for people with disabilities by 2024. [PDF file]. Available from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/government/about-the-bc-government/accessible-bc/accessibility-2024/docs/accessibility2024_update_web.pdf Traxler, J. (2016). Inclusion in an age of mobility. Research In Learning Technology, 24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v24.31372 (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site. W3C (2016). Accessibility. [Web page] available from https://www.w3.org/standards/webdesign/accessibility I seem to have occasion to repost my most viewed blog post to date once every few months, as the discussions around blanket bans on mobile devices in schools rear their ugly heads once again. This time, it's talk from the newly elected Progressive Conservative government in Ontario, Canada, who are placing a blanket ban on mobiles on the table as part of their incoming platform (Flanagan, 2018). (A few months back, it was the blanket ban on cell phones in schools in France (Willsher, 2017).) So... here it is again... reposted here so that this March 2016 post from my old blog site, the xPat_Letters Blog, has a new home (and new context) here on the brand new Power Learning Blog. Ban First, Ask Questions Later... The Problem with Calls to Ban Mobile Devices (updated) (originally posted March 2, 2016) I read the article Schools that Ban Mobile Devices See Better Results on the bus this morning. It is from May 2015, but someone had reposted the @guardian piece to my @Twitter feed. From my perspective as a mobile learning researcher, it presented troubling research findings: "Effect of ban on phones adds up to equivalent of extra week of classes over a pupil’s school year" (Doward, 2015) But, they’re not troubling for the obvious reason presented in the story. The premise of the story (and the research on which it was based) was that mobile devices are distracting students to the level of significant lost instructional time. And if schools want to see better test scores, then they had better start banning mobile devices. No. This is not the problem. A blanket ban on mobile devices because they distract learners is just the latest in a centuries-old trend of resisting technological change out of fear of the unknown. Steve Howard (2012, July 14) pointed out that as far back as 1815 a school principal fought against the introduction of paper and ink, and lamented that: Students today depend on paper too much. They don’t know how to write on a slate without getting chalk dust all over themselves. They can’t clean a slate properly. What will they do when they run out of paper? If we want to leverage new technologies to enhance learning experiences and bridge current inequities in the classroom, then we cannot succumb to knee-jerk reactions to alarmist statistics. As Homer Simpson once said: What IS troubling with this story (and research) are the questions that were NOT asked. The research shows an increase in achievement across ALL schools that have banned mobile devices versus ALL schools that allow them. BUT, no attempt is made to look at schools that actually plan for mobile technology integration. It could be that the majority of the schools polled have no such plans, in which case the argument that mobile devices only serve to distract students is likely true. But what of schools that have coordinated their technological infrastructure and pedagogical strategies to leverage mobile devices within the curriculum? I have predicated my mobile learning research to date on the problem that teachers and schools are the barriers to effective integration of mobile technologies because they lack confidence in the technology. The problem is NOT that mobile devices are allowed into schools. The problem is that we are not preparing teachers and schools for an environment of ubiquitous access to technology. From my dissertation (Power, 2015, p. 11): Ally (2014) noted that teacher training continues to be based on an outdated education system model that does not adequately prepare teachers to integrate mobile technologies into teaching practice. Lack of training in the pedagogical considerations for the integration of a specific type of technology can have a negative impact upon teachers’ perceptions of self-efficacy (Kenny et al, 2010). Technology will never replace good teachers. But technology can make good teachers better. Better teacher (and school) preparation will enable educators to make instructional design decisions that incorporate technology, and increase student engagement and access to learning opportunities and resources. My research has shown that professional development focused on scaffolding technology integration in the context of desired learning outcomes and appropriate pedagogical decisions does increase teachers’ interest and confidence in using educational technology. If teachers are interested, and plan how they will leverage technology in the classroom, then distraction will decrease and learning will improve. However, preparing teachers to leverage educational technology is not enough. We must also prepare students. Yes, if you let students who have had no guidance access mobile devices, then there is huge potential for them to be distracted. But, if you teach them digital citizenship and responsible use, there is less likelihood of distraction. And they will be better prepared for a world with near universal technology permeation. You cannot teach digital citizenship or responsible technology use with black and white policies of either banning all devices, or letting them all in. Unfortunately, the information technology support departments (and bureaucracies) of too many school systems (and higher education institutions) still operate with Acceptable Use Policies, which explicitly detail what is permissible and what is not. In contrast, Responsible Use Policies focus on making appropriate decisions about when and how to use technology. (Joe Countryman, Mary-Ann Vardakas & Melissa Taffe did a presentation on this, and prepared a wikipage about it for a Problem-Based Learning activity in the Digital Tools for Knowledge Construction course I teach at University of Ontario Institute of Technology.) Before policy makers, or the public at large, jump to the conclusion that the statistics presented in the Guardian (and also on CNN) point to the need for an outright ban on mobile devices in education, a number of questions should be considered:

References

Ally, M. & Prieto-Blázquez, J. (2014). What is the future of mobile learning in education? Mobile Learning Applications in Higher Education [Special Section]. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento (RUSC), 11(1), 142-151. doi http://doi.dx.org/10.7238/rusc.v11i1.2033 Countryman, J., Vardakas, M., & Taffe, M. (2016). Acceptable use policies. Retrieved from http://educ5101jmm.pbworks.com/w/page/104432989/PBL%201%20-%20Group%204%20-%20Acceptable%20Use%20Policies Doward, J. (2015, May 16). Schools that ban mobile phones see better academic results. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/may/16/schools-mobile-phones-academic-results Flanagan, R. (2018, May 30). PC platform includes ban on cellphones in schools. CTV News Kitchener. Retrieved from kitchener.ctvnews.ca/pc-platform-includes-ban-on-cellphones-in-classrooms-1.3952316#_gus&_gucid=&_gup=twitter&_gsc=Qi5DSUU Howard, S. (2012, July 14). The ruin of education in our country – A positive thing [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://stevehoward999.wordpress.com/2012/07/14/the-ruin-of-education-in-our-country-a-positive-thing/ Kenny, R.F., Park, C.L., Van Neste-Kenny, J.M.C., & Burton, P.A. (2010). Mobile self-efficacy in Canadian nursing education programs. In M. Montebello, V. Camilleri and A. Dingli (Eds.), Proceedings of mLearn 2010, the 9th World Conference on Mobile Learning, Valletta, Malta. METTL (2015). The Homer Simpson guide to online assessments [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://mettl.com/blog/2015/08/the-homer-simpson-guide-to-psychometric-assessments/ Power, R. (2015). A framework for promoting teacher self-efficacy with mobile reusable learning objects (Doctoral dissertation, Athabasca University). Available from http://hdl.handle.net/10791/63 Power, R. (2016, March 2). Ban First, Ask Questions Later... The Problem with Calls to Ban Mobile Devices. [Web log post]. The xPat_Letters Blog. Available from http://robpower74.blogspot.com/2016/03/ban-first-ask-questions-later-problem.html Willsher, K. (2017, December 11). France to ban mobile phones in schools from September. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/11/france-to-ban-mobile-phones-in-schools-from-september  If you've ever visited my site before, you may be asking "why the changes?" I've just completed the daunting task of rebranding from robpower.weebly.com to powerlearningsolutions.com -- and I'm excited about the change! So, what prompted the shift? Well, I got inspired after reading a blog post by Tim Slade titled 5 Tips for Elevating Your eLearning Career. Now, it's not that I think my career is stagnating... especially in light of this awesome feedback two of my students from a graduate-level EdTech course recently posted on Twitter: After reading Tim Slade's blog post (he really has a great blog, BTW!), I just got to feeling that my personal website had remained unchanged for far too long! I also got to thinking about the whole point of my site. I want it to be more than just an ePortfolio. And, I've been paying for the Power Learning Solutions domain name and URL for some time now, without actually using it for anything (I snatched it up with the intent of creating a website as a home for eLearning consultation work). So... I figured that the time had come to shift the focus away from just "Rob Power," and to put it onto the work that I do with educational technology, instructional design and development, mobile learning, and helping to prepare teachers to effectively leverage technology in their teaching and learning practice. The icon at the top of this post (which is one that I have been using for some time now) is a reflection of the overall rebranding -- as it symbolizes using educational technology to "push play," and put the world at our fingertips!

The End of xPat_Letters? So, now I'm left with the burning question... what do I do with my Twitter handle (@xPat_Letters)? I've been using that handle for several years, and have just broken the 1K follower mark. I know that I can update my handle without losing my followers... but it's hard to break the attachment! I created the handle when I lived and worked overseas at College of the North Atlantic-Qatar. I kept it after returning to Canada, as I felt it was still fitting. I might not be a geographical expat anymore -- but I still consider myself a digital expat. I'm not a digital "native" -- rather, I'm someone who's chosen to travel into the wonderful world of educational technology, and to experience all that it has to offer! But, I think that I will make the leap, and update my Twitter handle now, too. As part of my digital rebranding, I'll likely just take the leap within the next day or so! I'll also be taking the leap, and shifting blogging profiles (and strategies). I've been using Blogger for several years -- though I'll admit that I haven't been a very frequent blogger. Perhaps a new direction that I might take -- as I shift from my old xPat_Letters Blog to this new platform (integrated directly into the Power Learning Solutions website here in Weebly) -- is to start focusing more on creating posts to share educational technology tips, tricks, and resources! In the meantime, you can check out some of my older posts over at http://robpower74.blogspot.com/ Welcome to the new Power Learning Solutions! References: Power, R. (2018). The xPat_Letters blog. [Web log]. Available from http://robpower74.blogspot.com/ Slade, T. (2018, June 2). 5 tips for boosting your eLearning career. [Web log post]. TimSlade.com. Available from https://timslade.com/blog/elearning-career/ |

AuthorRob Power, EdD, is an Assistant Professor of Education, an instructional developer, and educational technology, mLearning, and open, blended, and distributed learning specialist. Recent PostsCategories

All

Archives

June 2024

Older Posts from the xPat_Letters Blog

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed